Jewish History from the Archives of Florence and Cremona Part I: The Medici Archives

Fact Paper 38-I

© Samuel Kurinsky, all rights reserved

Summary: The Medici archives, now being catalogued, contain thousands of documents pertaining to Jewish and Sephardic culture, commerce and industry. The Medicis granted Jews freedom to live and trade in Leghorn and many privileges in Florence, Pisa and elsewhere in Tuscany.

- Research in Cremona and Tuscany

- The Medici Archives

- The Medici Project

- The Judaic Connection

- The Jews and the Medici; An Historical Summary

- The Medici Archive Project's Judaic Initiative

- Typical Medici Documents Relating to Aspects of Jewish History

- The Following Fact Papers on Cremona and Tuscany

- Notes

Research in Cremona and Tuscany

The Jews of the Provinces of Cremona and Tuscany enjoyed the protection of two Grand Dukes, the Gonzagas of Mantua and the Medicis of Florence. Between the mid-sixteenth and mid-eighteenth centuries the noble rulers of the Cremona and Tuscan regions demonstrated their pragmatism by extending tolerance to the Jews while the Inquisition was still rampant, thereby gaining the economic advantages Jews were able to offer their regimes.

Father Franco Bontempi, whose researches into the contributions of the Jews to the economic and cultural development of the region of Brescia was reported on in Fact Paper 34, likewise researched the role of the Jews in the contiguous Cremona region. "Don Franco" has now authored a book on the subject: Cremona e Gli Ebrei ("Cremona and the Jews"), in which the results of his dedicated research is documented in scholarly detail.

Don Franco delved into files relating to the Jews of the Brescia and Cremona regions that have never been explored before. The book will shortly be published by the Province of Cremona. Don Franco sent us a copy of his manuscript, and a scoop on his work will be offered in the subsequent Fact Paper issue.

Don Franco's research parallels that of the Medici Archive Project, reported on in The Hebrew History Federation's Newsletters 58, 60 and 66. In fact, correspondence between the two dukedoms relating to the Jews appear in both archives. Some curious aspects of this intercourse are revealed in the Medici files, indicating that the two regimes shared a respect for Judaic talents.

For example, there is the case of a Jewish actor from Mantua, Simone Basileo, Hebreo, who was granted permission by Grand Duke Cosimo II in 1611 to travel and perform around Tuscany

The actor's full name was Simone Shlumiel ben Shlomo Basilea. Collaborating with the famous composer Salamone de Rossi, Basileo (also: Basilea) participated in an important performance in 1605. By 1615 he had become the head of a committee that arranged the production of Commedie and other Spectacoli at the Gonzaga court in Mantua.1 The newly-revealed Medici correspondence shows that Basileo and his company of actors and musicians were invited to tour Tuscany in the interim period, and to do so without an identifying badge, a privilege they had likewise enjoyed in Mantua.

The exemption from wearing a segno, or badge identifying him as a Jew, was extended from Mantua to Tuscany by Cosimo II on the 10th of March, 1611:

"The Jew Simone Basileo," states the Patente issued by the Duke, "has demonstrated his talent and his diligence while performing some plays. Therefore, it is our wish and our pleasure that he be allowed to travel, to sojourn, and to perform plays in any city or in any other place in our State. Furthermore, neither he nor his companions shall wear a distinguishing badge, on their hat or elsewhere. Officials shall not hold this against them or hinder them in any way, but shall offer them the assistance that such ability merits."2

This Fact Paper 38-I begins by reviewing and updating the results of the Medici Archive Project. The sequel, a digest of Father Franco Bontempi's Cremona e Gli Ebrei, will follow (Fact Paper 38-II). These papers, along with the history detailed in Fact Paper 34 The Jews of Brescia, Fact Paper 24, The Jews of Casale Montferrato, and Fact Paper 25, The Glassmakers of Altare, complete an arc from Florence through Piedmont into Cremona and Brescia in which the Jews enjoyed a limited but extraordinary tolerance for the two centuries in which the Inquisition was at its most virulent.

The Medici Archives

The May and July/August 1996 issues of the HHF Newsletters 58 and 60 respectively reported on the circumstances in which the HHF became associated with the Medici Archive Project.

The Medicis are renowned as Europe's most brilliant and influential family of art patrons. For scholars, artists and connoisseurs, no less than for tourists, a visit to Florence is largely a pilgrimage to Medici patronage. The churches, monasteries, palaces and gardens that were built or endowed with art works during their reign, and the dynastic art collections now housed in the Uffici and Pitti palaces, are among the world's greatest treasures.

The archive of the Grand Dukes of Tuscany (1532 - 1743) is likewise a great cultural trove of the period. This vast treasury of documentary material, now preserved in the Florentine State Archives (FSA), includes private and government correspondence, inventories, account books, maps and drawings. They have survived virtually intact, forming the most comprehensive record of any princely regime of the Renaissance.

The Medici Granducal Archive (Archivio Mediceo del Principato) consists of 6,429 massive folders containing over 300,000 documents and 3,000,000 letters. Included is the correspondence of the Medici family, the documents of the granducal administration, and the records of the Tuscan diplomatic service from 1537 to 1743.

Although the Medici archive is obviously essential to an understanding of the Renaissance and of the evolution of western culture, it has remained largely inaccessible to scholars, due to the lack of catalogs and inventories. Until the formation of the Medici Archive Project, less than five percent of this material had been accessed.

The Medici Project

The Medici Archive Project (MAP) was founded in 1993 by Dr. Edward L. Goldberg, an American art historian resident in Florence. Albeit the project was funded for augmenting art history, Jewish studies evolved as a important adjunct to the project.

"I started the Medici Archive Project in the spring of 1992." wrote Dr. Goldberg to the HHF in describing the project. "By then, I had already worked in the Archivio di Stato Fiorentino for nearly twenty years, since my days as a graduate student. The Project's first initiative was the Guide to Art Historical Sources in the Medici Granducal Archives (1532-1743). This seemed the ideal place to begin, since I am an art historian and the Medici are best known as patrons of the arts."

"The experience of working with the Medici Granducal Archive has always seemed slightly larger than life to me, characterized as it is by extraordinary rewards. Not only are the Medici the most extraordinary family in the history of European culture, they are also the best documented. During the two centuries of granducal rule, these princes and their secretaries saved virtually every scrap of paper that passed through their hands, whether relevant to the Medici government, to the administration of the Medici household, or to the personal affairs of the Medici family. In addition to account books, legal documents and administrative records, we have approximately two million letters [later upscaled to three million], to and from the Medici and their secretaries -- describing the interaction of tens of thousands of individuals with Medici connections, throughout Europe over the course of two hundred years."

"This unique fund of epistolary material has come down to us virtually intact -- but unfortunately, it is still largely unindexed, with no rational system for access and retrieval. It thus remains out of reach to all but a few intrepid scholars -- those who can afford the months and even years needed to learn their way around."

The Judaic Connection

Dr. Goldberg's astonishment at finding a wealth of correspondence between and about the Medicis and the Jews after a cursory initial survey inspired a realization that its Judaic historical aspect merited special consideration, investigation and research.

"For me personally," wrote Dr. Goldberg to the HHF, "the most exciting surprise in the Medici Granducal Archives has been its rich documentation of Jewish life, not only in Tuscany, but throughout Europe, North Africa, and the Near East. Until now, the study of Tuscan-Jewish history and culture has been based almost exclusively on notarial records, tax documents and judicial proceedings -- files that are more easily accessible to scholars, but usually of a dry and impersonal nature, giving little sense of the real people and the real issues involved in historical situations. As the enclosed sample documents demonstrate, a fuller and more compelling history of Jewish life in Tuscany remains to be written, based on the discoveries of the Medici Archive Project."

"In the course of current work in the Medici Granducal Archives, the Medici Archive Project is finding a vast range of unstudied and unpublished documentary sources relevant to Jewish life. At present, Project researchers are able to make only hasty notes on this material, since it is outside the scope of current Project funding, which has been allocated specifically for The Guide to Art Historical Sources in the Medici Granducal Archives (1532-1743.)"

"The Medici Archive Project offers an exceptional -- and probably unrepeatable -- opportunity for the advancement of Jewish Studies. An experienced archival research team is now at work in the Archivio di Stato Fiorentino, methodically sifting the source material there and identifying the documents of Jewish interest. The most difficult, expensive and time-consuming part of the job is thus already under way."

"In order to bring this unique Jewish material into the mainstream of current scholarship, it is necessary to transcribe the relevant documents and publish them in a definitive edition. This edition will include (1) scholarly introductions, (2) explanatory notes identifying names, places and other references in the documents, and (3) full indices."

"In order to achieve this monumental publication, it is necessary to expand the Project's current research team to include scholars specialized in Italian Jewish history. As more and more Jewish documents are discovered in the course of Project work, these will be turned over to appropriate specialists for transcription and annotation. The Medici Archive Project will assume responsibility for the administration, editing and publication of The Documents for Jewish History, Religion and Culture in the Medici Granducal Archives."

Dr. Goldberg concluded that "It is clear that our two organizations share many interests and goals, and I look forward to a long a fruitful collaboration."

Subsequent revelations by Dr. Goldberg and his associates justified his initial assessment of the importance of the archive to Judaic history. Dr. Goldberg submitted the following background paper to the Hebrew History Federation Ltd. to illustrate the potential Jewish historical relevance of the new MAP initiative. The paper is entitled:

The Jews and the Medici; An Historical Summary

"The fate of Tuscan Jewry, in the early modern period, was inextricably linked to the favor and fortune of the House of Medici. Though a Jewish presence was registered in Lucca as early as the ninth century and a network of Jewish banks had spread throughout the region by the mid-fifteenth, the stable "Israelite Communities" of Florence, Siena, Pisa and Livorno were political creations of the Medici rulers. Like the Medici Grand Dukedom itself, these communities took shape in the course of the sixteenth century."

"In the 1490's, under the Catholic theocracy of Fra Girolamo Savonarola, both the Medici and the Jews were expelled from Florentine territory. When the Medici returned to power in 1512, the Jewish ban fell into abeyance, until the next expulsion of the Medici in 1527. In 1537, Cosimo de 'Medici seized definitive control of the Florentine government and reorganized it as a princely state -- the Grand Dukedom of Tuscany. This state flourished for two hundred years, under seven successive Grand Dukes: Cosimo I, 1537-1574; Francesco I, 1574-1587; Ferdinando I, 1587-1609; Cosimo II, 1609-1621; Ferdinando II, 1621-1670; Cosimo III, 1670-1723; Gian Gastone, 1723-1737."

"As a sovereign ruler, Cosimo I was free to dictate new terms of Jewish resettlement, according to his own best interests and that of his regime. Coming from a merchant family himself, Cosimo I recognized the vast potential of Jewish capital and Jewish entrepreneurship, dispersed by the Iberian expulsion of the 1490's, and yet to be integrated into world commerce. By the mid-1540's, less than ten years after he gained the throne, Cosimo I began recruiting affluent Spanish and Portuguese Jews for resettlement in his affluent city of Florence and his chief port city of Pisa. Tuscany appeared as a haven to many displaced Italian Jews as well, particularly after the final expulsion of the Neapolitan community in 1540 and the creation of ghettos in the Papal cities of Rome and Ancona in 1555."

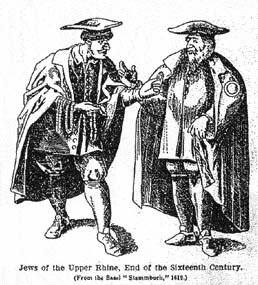

"Though the Grand Dukedom of Tuscany was viewed by Jews as a "liberal" state, Medicean liberalism was limited in scope and pragmatic in principle. After actively courting the Jews in the 1540's and 1550's, when an injection of capital was desperately needed, Cosimo I began retrenching in the 1560's and 1570's, as political relations with Spain and the Papal State became paramount. In 1567 he reimposed badges of identification for Jews, in 1569 shut the Jewish banks, and in 1570-71 restricted Jewish settlement to two new ghettos in Florence and Siena."

"In practice, Medici rule was characterized by a shifting balance of privileges and concessions, and for Jews in Tuscany the door was never as open nor as closed as it might seem. The great "special case" was that of Livorno. In 1593, less than a quarter century after Cosimo I ghettoized his Jewish subjects, his son Ferdinando I granted them free residence, unlimited access to trade, and even partial self-government in this new Medicean free-port on the Mediterranean.:

"The Livorno experiment was a triumph of enlightened self-interest for both the Jews and the Medici. Indeed, this thriving commercial hub became so essential to the Tuscan economy that even Cosimo III (1672-1723), the most bigoted of the Medici Grand Dukes, had little choice but to respect Jewish rights there. Vast fortunes were made by the Iberian merchant aristocracy that gave Livorno Jewry its particular culture and character. However, the Livorno community also included levantini from Turkey and North Africa, Ashkenazi from Northern Europe and Italian Jews of various origins."

"In addition to banking and trade, especially with the East, the Jews of Livorno developed diverse manufacturing enterprises. In the late sixteenth century, Maggino di Gabriele moved his glass and silk factories there from Pisa, in order to take advantage of the new freedoms. The Jews of Livorno established a monopoly on the Italian production of coral, which they frequently used to ornament their own liturgical objects. In 1632, they imported the first coffee into Italy and then opened the first coffee-houses. In 1650, Jedidah Gabbai founded a Hebrew press in Livorno, giving rise to a major Jewish printing industry that supplied the Sephardic communities of North Africa and the Near East."

"Though Livorno was a major center of Jewish commerce, second only to Amsterdam, it was also a leading center of Jewish study and mysticism, particularly under the influence of Rabbi Joseph ben Emanuel Ergas (1685-1732) and other proponents of the Kaballah. Indeed, the Jews of Florence, Siena, Pisa and Livorno were conspicuous for the breadth and diversity of their interests and activities. Vitale Nissim de Pisa, from one of the oldest banking families in Tuscany, was a distinguished Talmudist and his son Simone graduated as a Doctor of Medicine

from the University of Pisa in 1554. Another medical doctor, Mosè Cordovero, was among the pioneers of banking in Livorno around the year 1600. Elia Montalto di Luna, in the early seventeenth century, practiced medicine at the Medici Court while writing treatises on ophthalmology, astronomy and comparative religion.""These references to people, places and events are only notes for a larger history of the Jews in Tuscany -- a history that for the most part remains to be written. In regard to the crucial two centuries of Medici rule (1537-1737), eloquent new documents are now being discovered every day, in the course of work in the Medici Archive Project."

(End of submission by Dr. Edward L. Goldberg).

The Medici Archive Project's Judaic Initiative

A new MAP Initiative, Jewish History, Religion, and Culture in the Medici Archives was officially launched at a cocktail party held at Sotheby's on January 27th, 1997, in connection with a private viewing of Old Master paintings and eight paintings from the collection of Saul P. Steinberg.

A list of 43 "patrons" (donors of $5000 or more) to the latter project was announced on the literature distributed at the viewing. Also presented (and present at Sotheby's) were the honorary patrons: His excellency Ferdinando Salleo, Italian Ambassador to the United States and Minister Franco Mistretta, Consul General of Italy in New York. Three committees, International, American and Florentine were formed, consisting of professors and scholars from 25 universities and museums..

While surveying the immense range of material, MAP's research team has been systematically retrieving all references to Jews and Jewish affairs. Virtually all of this unique documentation, which touches upon Jewish activity throughout Europe and the Mediterranean world, is currently unknown to scholars and writers, since it was unindexed and dispersed throughout a vast archive of what turned out to be three million documents. No one had heretofore attempted to cull out material related to the Jews.

Although there is evidence that Jews were present in Tuscany in the Roman period, and documentation of Jewish presence date from the ninth century, the stable "Israelite Communities" of Florence, Siena, Pisa and Livorno (Leghorn) were political creations of the Medici Grand Dukes of Tuscany. In 1570-71, Grand Duke Cosimo I del Medici instituted a semi-autonomous Ghetto in Florence that functioned until the end of Medici rule. In 1593, Grand Duke Ferdinando I del Medici granted full religious, civil and commercial rights to Jews of all nations in the new Tuscan free port of Leghorn, which developed into the most prosperous and cosmopolitan community on Italy.

The archival documents cover the full range of Jewish life in Tuscany and a great deal more. The Grand Dukes and their agents were in touch with Jews throughout Europe and the Mediterranean, including merchants, bankers, sailors, craftsmen, doctors, scholars, rabbis, actors and art dealers. MAP is therefore revealing eyewitness accounts of Jewish industrial, commercial and cultural activity across Italy and in France, England, the Netherlands, Germany, Spain, Portugal, North Africa, Turkey, the Balkans, and the Near East.

MAP is preparing three publications;

- Documents for Jewish Religion and Culture in the Medici Granducal Archive: a complete scholarly edition of all letters relevant to Jewish life in the Granducal period.

- The Birth of the Florentine Ghetto: a complete scholarly edition of the papers of the Granducal Commission that instituted the first Florentine Ghetto in 1570-71

- Jewish Voices in the Medici Archive: a richly illustrated book for the general reader, describing Jewish life from the fifteenth through the eighteenth century as documented in the Medici Archive.

Included in the material are the same names of a number of the families as those with glassmaking branches cited in my articles in the Italian scientific journal, Alte Vitrie.

Of particular relevance is the connection between the silk making and glassmaking industries of Pisa and those of Genoa. I found seventeen documents in the Genovese archives relating to Jews who had been invited back to settle in Genoa a century after the Jews had been expelled from that city. Several of these documents record the granting to a group of glassmaking Jews from Tuscany of the exclusive right to produce glass and glassware in the entire dominions of Genoa for period of 25 years.

Also found was evidence that the cultivation and processing of silk was yet another outstanding Jewish industry that came up from Tuscany into Genoa, Piedmont, Mantua, and Cremona. Medici documents substantiate the theory that Jews were seminally involved in both the sericulture and vitric arts of Tuscany. One late sixteenth century document, for example, grants Maggino di Gabriele, a Jewish entrepreneur, the right to move his glass and silk factories from Pisa to Livorno.

Cremona, in the heart of the Po Valley, did not have native materials conducive to glassmaking. But the Po Valley did provide the environment for growing mulberry trees, and therefore for sericulture. The road into nearby Casale Montferrato was known colloquially both as "Mulberry Road," and as "Jews Alley." The Sicily-Pisa-Genoa-Cremona itinerary of sericulturist Jews have thus been completed by the work of MAP in Tuscany on the one hand, by me in Piedmont on the other, and now by Father Franco Bontempi in Cremona further along the route. It is also evident that the Jews carried the art on into the Veneto.

Typical Medici Documents Relating to Aspects of Jewish History

In terms of religious tolerance, it is interesting to note correspondence from one Granducal secretary to another about a "Jewish" gentlewoman who called on Duke Cosimo and Duchess Eleanora de Toledo in 1544. They had a good discussion, he reported, on "religious matters."3

The "Jewish Gentlewoman" appears to have been Benvenida Abravanel, wife of Samuel Abravanel. Samuel had been head of the Neapolitan Jewish community before its final expulsion in 1540. Benvenida's uncle, Isacco Abravanel, had been financial advisor to the King of Portugal and served in a similar capacity thereafter to King Ferdinando and King Alfonso II of Naples.

During her husband's tenure in Naples, Benvenida tutored Eleanora, the daughter of the Spanish Viceroy of Naples. That intimate relationship between Benvenida and her highly-placed pupil continued after Eleanora married Duke Cosimo I.4

Such discussions of "religious matters" at high levels of the Ducal court could well have been the basis for accusations of Judaizing against members of the Abravenel family. Such accusations are usually made against Jews who were baptized as Catholics and who reverted to Jewish identity. The Duke himself undertook to wrest the Abravanels from the talons of the Inquisition. In a heretofore unknown letter of 1563 from Duke Cosimo di Medici to Cardinal Alesandino, the Duke invokes the prestige of his powerful office in protecting Benvenida's son, Jacob Abravanel, and his wife Gioia, against a false accusation of Judaizing:

"Jacob Abravanello and Gioia his wife have always lived as they do now, under the code of Jewish law, and they have never professed themselves Christians. However, a person has made this charge against them, persecuting them out of greed for their possessions and not from the zeal to do good. Since they have come to live in my State, I cannot fail to defend them from unjust persecution nor allow them to be ruined through the avarice of others. Your most Reverend Lordship knows me, and I trust you will be equally ready to support and assist me in this matter, and I address you without ceremony."5

The matter was dropped!

The tolerance of Jews in granducal Tuscany, Mantua, (and for a short time, also in Ferrara) was frequently tested by dire warnings. A 1569 letter from the Tuscan ambassador to Madrid to Crown Prince Franceso de 'Medici reports:

"... In Lisbon there is now the plague, which wreaks no little havoc, leaving more than thirty dead every day. Though that might seem no great thing [sic!] considering the size of the city, some persons who are of the Jewish race are taking this opportunity to flee from there in order to resume the faith of their fathers elsewhere -- even though they were baptized and lived as Christians against their will. Some of them are heading to Italy, where they hope to be treated like Marani in Ferrara. Those that receive them, however, should be aware that they are apostates and not Jews. Since they had all been in Spain, where no Jews are allowed, it is certain that all of them underwent baptism..."6

The common interest of the Dukes of Mantua and Tuscany in protecting Jews was invoked in a series of letters, one of which went from Cosimo de Medici to the Duke of Mantua dated 1565. In it expresses support for Ventura di Moise, a Jew from Perugia studying at Pisa University "since he is a man of talent." The Florentine Duke thus renders moral validation to the Mantuan Duke's tolerant treatment of Jews. Cosimo did not end his correspondence with a letter to Mantua. He expressed his support for Ventura de Moise in letters to the Florentine ambassadors in Rome and Ferrara, to the Duke of Ferrara, to the Duke and Duchess of Mantua, to Cardinals Este, Nicolino, Savello and Vitelli! "Your Lordship sees," the Duke's letter to the latter Cardinal states, "how much I confide in you, since I press the claims not only of friends and Christians but of Jews as well."7

Ventura de Moise da Perugia is known from rabbinical sources, and this correspondence adds a fascinating new dimension to the story of the controversial young man. "Ventura (called Shemuel in the Hebrew documents) was betrothed to marry a young woman named Tatar in Venice, daughter of the eminent doctor Yosef Tamari. Several months after the betrothal, an argument ensued between Shemuel and his father-in-law. Shemuel then left Venice, abandoning the woman he was engaged to marry and leaving her unable to marry anyone else under Jewish law. Many prominent rabbis involved themselves in this case, issuing writs of excommunication and requesting th support of sovereign rulers in enforcing them."8

According to the historian Umberto Cassuto, Shemuel.Ventura settled in Florence and became a librarian in the Ducal Biblioteca Laurenziana.

It appears that some Jews became students at the University of Pisa by special dispensation and were sometimes allowed to earn degrees, especially in medicine. It is significant, and surprising, to now learn that "Jews were freely admitted to the University of Siena from 1543 to 1695, and took degrees in medicine and philosophy."

Already mentioned above in the context of the sharing of tolerance between the two Dukedoms is the patente granted to the Jewish actor and impresario, Simone Basileo Hebreo, by Grand Duke Cosimo II, granting Simon and his Jewish company the right to travel and perform throughout Tuscany without an identifying badge.

Cosimo de Medici was also in contact with Venetian Jews. A letter dated 1561 is about antique medals he had acquired from Jacobiglio, a Jewish trader in Venice. In it Cosimo agrees to pay for the gold and silver ones, and to accept the bronze ones as a gift.9

The relationship between Duke Cosimo I de Medici and Jacobiglio Hebreo was of long standing and is detailed in numerous other letters from 1554 to 1564. Jacob, based in Venice, evidently had commercial family connections in Constantinople, and dealt with classical coins, medals, cameos and engraved gems. The ancient connection Jews maintained with the production and commerce of precious objects (as was noted by Lois Rose Rose in Fact Paper 20-I, Ornament and the Jews), is placed well in evidence by this correspondence.

The commercial aspect of the relationship between the Medicis and the Jews is of paramount historical importance. Most illuminating is the manner in which Ducal correspondence was rewritten to circumvent Spanish roadblocks to international Jewish commerce at a time when the Grand Dukedom of Tuscany had become a Spanish client state. The crux of their relationship was an anti-Turkish naval alliance.

The attempt to outwit the Spaniard court in favor of Jewish trade is revealed in several drafts of a letter to be sent in 1576 from Grand Duke Franceso I of the Tuscan court to the Ambassador at the Spanish Court. Francesco was seeking permission from Philip II of Spain to allow Levantine Jews to tranship goods through Livorno. During this period The Levantini were Sephardic Jews from the Near East and North Africa who would have been considered Turkish subjects and were thus liable to Spanish harassment.

The first draft was direct: "Certain very rich Levantine Jews have offered to route much mercantile trade through our port of Livorno, if they can be assured that His Majesty will not disturb their goods on Venetian, French, and Ragusan ships." Then Francesco added a sweetener to his request. "With this opportunity to trade, they promise to keep us informed of the Turks plans and actions.

Evidently judging that this sweetener was not convincing enough to tempt the Spanish king to overlook

the Jewish aspect of the commerce, the paragraph was cancelled and was substituted for with a version which made commerce a mere ploy for espionage:

"I have negotiated with certain Levantine Jews in order to in order to learn all of the Turk's plans and what is happening in that part of the world, so that I can report this to his Majesty. This activity will take place under the cover of mercantile trade, for which they will keep a resident agent here, to receive correspondence and to carry out [canceled out word: mercantile] affairs, so they will not be suspected of designs of their own in these parts. His Majesty needs to issue a safe-conduct pass addressed to vessels under his command and made out to [cancelled out Jewish name: Lechier Machai] to those whose names are enclosed here."10 In the first memorandum, Francesco I informs Philip II that he is negotiating a lucrative transhipment contract with Levantine Jews for the port of Livorno, and the quid pro quo for the Spanish would be valuable intelligence on Turkish affairs. In the second version, the Grand Duke attempts to conceal his predominantly commercial motive, proposing to found a spy-ring under the cover of merchant activity.

Other unsent canceled passages strengthen the conclusion that Don Francesco de Medici was using the spy ploy simply to gain commercial advantage for himself. It is unclear how much of a commitment was actually made by the Levantini. What does blazon out of this and other documents is the far-reaching importance of the Jews in the international trade of every major port of Europe.

The significant role of the Jews in international commerce of the times is borne out by the documentation of efforts by the Medicis to obtain Judaic commercial, industrial and technological expertise.. These documents demonstrate the exceptional internationalism of European Jewry and their influence, for the Medici's efforts extended through Tuscany, Portugal, France and the Netherlands

The documents shed light on how Duke Cosimo de 'Medici engaged in secret negotiations to attract Jewish capital to his State, and convey the tone of cynical opportunism that characterized Jewish resettlement, even in the "liberal" state of Tuscany.

One such document is a diplomatic missile from Giorgio Dati in Antwerp to the Ducal Secretary in Florence about the elaborate plans for secretly inducing rich Portuguese Jews to settle in Tuscany through the renowned Mendes family, during a period in which the family was encountering legal difficulties in the Netherlands.

HHF Fact Paper 38, Jewish Women Through the Ages, described the difficulties the Mendes family encountered in leaving Spain, in transferring the family's assets to Amsterdam, then to Venice and finally to Turkey. The importance of the family, and of the head of the family, Doña Gracia Mendes, renowned as La Senora, to Jewish history was thoroughly covered by Cecil Roth in three scholarly works.11 The Medici archives provide a new and fascinating facet to this extraordinary history

The avidness with which the Medici's sought the immigration of the Mendes or other such Jews is made evident in the correspondence carried out in secret by granducal emissaries. Giorgio Dati was such an emissary in Antwerp, where La Senora and her entourage had sojourned on their escape from Portugal. Giorgio wrote:

"...In [a previous letter sent by courier] I told you it would be well to contact Mendes' people through their friends in Lyons, proposing that they leave here [Antwerp] with their assets. Gia Micches and Giulielmo Fernandez are the administrators for the Mendes and all their holdings, and the Salviati and the Pantiatichi are considered to be their friends.12 I also mentioned the court's great diligence and the firm proposals that were made to those Mendes in order to effect their return... The general opinion is that others of their nation are about to follow the Mendes, since they are leaders and the chief people."

"...You should know that I heard of a certain person who is close to the Mendes. Through confidential channels, I found someone who could speak to him, leaving me personally unaware of what was said. This was so that he would write to the Mendes, offering them a place of sojourn and guarantees of security, on behalf of a great Italian prince -- but proceeding cautiously, and not naming that prince until a more appropriate moment."

"... He could speak freely to me, I told him, since they are a highly suspicious people, and they are now more afraid than ever of giving themselves away. Once we started talking, he opened up enough for me to convey your message..."

"...He said that if we made the effort in Portugal and spread the word there, we could attract many rich and substantial men (New Christians, that is to say.) If these were given guarantees, and shown where they would live and shown that they would be able to engage in commerce, they could be induced to leave [Portugal], if the matter was handled cautiously."

"... Among other things he asked me how far Pisa was from Florence. He had heard that Pisa was well-situated for Spain, Portugal, Naples, Rome and other places by sea, that it was a fine and abundant place to live and houses were cheap, that there were many gardens and other such considerations. Not only did I confirm all this but I magnified the qualities of that city, saying that his Excellency [Duke Cosimo de Medici] valued it as much as his own right eye, and that he has instituted a find university there."

[One of the enticements Giorgio.Dati held out to his contact in Antwerp was the possibility of Judaic attendance at Duke Cosimo's University in Pisa]

"...I also conferred with a man of substance who recently returned from Portugal, where he had stayed for three years. He is of that country, very well-informed regarding things there and what is more, has a close friendship with the leaders of the sect of New Christians. He confirmed that it might really bear fruit, attracting such New Christians who have lots of money, as long as we can demonstrate that their persons and their property would be secure, that they would be well treated, and that their behavior would not be scrutinized too closely. You know how distrustful these New Christians are about the way they live their lives."

"...If he closes the deal successfully, he would want special compensation from His Excellency, as his usual for those who carry out dangerous, even life-threatening assignments. My friend's business in Antwerp earns him three or four hundred scudi a year, but he will set this aside as soon as he hears that His Excellency requires his services.... If he enlists one of their leaders, he thinks that this leader will eventually attract an infinite number of those who are rich and loaded with cash

Though I know your prudence well, I beg you and I caution you to keep this matter as secret in Florence as we are keeping it here in Antwerp, where no one is privy except that friend of mine... Therefore I await your confidential reply, begging you to keep me in his Excellency's good graces.

From Antwerp on the 26th in October 1545; Your Lordships servant, Giorgio. Dati Giorgio then added a post script:

"...I gather that on the first of September next year that law expires in Portugal which for ten years impeded the Inquisition from proceeding against the behavior of New Christians, without direct evidence or first-hand testimony. When this law expires, the Inquisition can act on clues and conjectures and so forth. This will force many rich people to leave, not wanting to tempt fate with legal decisions of that sort, and they will seek new and more favorable places of residence. Many pass through here every year with the spice fleet from Portugal, before disbursing to various places..."

Illustration from Fact Paper 36, Jewish Women Through the Ages.

The Medici archives go far to document the value princes of Europe placed upon Jewish participation in the economies of their realm and the devious methods often used to circumvent church strictures in order to avail themselves of their expertise and entrepreneurship. This value remained despite the Jews having been driven from the manual trades, denied the ownership of land, subjected to burdensome taxation, expelled from their homes and country and suffering recurrent confiscations of their property.

The Following Fact Papers on Cremona and Tuscany

There was nothing in the Province of Cremona equivalent to the massive Medici archive. To reconstruct the contribution of the Jews to the commerce and culture of the region, Father Franco Bontempi had to cull through the ill-kept and incomplete records of some 50 towns, villages and districts for relevant material. The result is nonetheless revelatory. Don Franco's work, Cremona and the Jews, to be reviewed in the subsequent Fact Paper 38-II opens yet another window into the rich cultural heritage of the Jews.

Subsequently, an update on Jewish artisanship and entrepreneurship from the Medici files will follow as the research advances. For example, an important facet of Jewish activity relates to textiles and costumes. The researchers at MAP report that: "By the early sixteenth century the mass production of woolen cloth in Tuscany had already given way to a smaller and more luxurious commerce in silks, brocades, fine linens, embroideries, trimmings and specialty fabrics... The Medici Granducal Workshops planned and produced lavish state gifts of apparel and textile furnishings that were treasured by princes and courtiers throughout Europe. This essential aspect of Tuscan diplomacy is eloquently documented in the Medici Archive."

It remains to be seen how significant a role Jews played in the production of and trade in Tuscan luxury textiles.

Notes

- S. Simonsohn, History of the Jews in the Duchy of Mantua, Vols. I-II, Jerusalem 1962-4 (Hebrew) 665ff.

- Cited from the Archivio di Firenze, Mediceo dei Principati (FSA) 303, f.99r.

- "Disputando alcuni belle cose delle fede."

- FSA 1171, f.226r.

- FSA 218, f.35r-v.

- FSA 4898, ff.514v-515r.

- FSA 226, f.37.

- Notes by MAP from Simonsohn, Ibid, 501-504.

- FSA 213, f.43v.

- FSA 1170a, Insert III, ff. 171-172v.

- Cecil Roth, (1) The House of Nasi, Doña Gracia. (2) The House of Nasi; The Duke of Naxos (3) Doña Gracia of the House of Nasi. All are published by the Jewish Publication Society of America, 1948, 1949, and 1988 respectively.

- A branch of the Salviati family became one of the great glassmaking families of Murano.