Glassmaking: A Jewish Tradition Part III: Flint Glass and the Jews of Genoa

Fact Paper 6-III

© Samuel Kurinsky, all rights reserved

- Lead Glass Introduced into England

- The Dagnia Family

- Vitreum Plumbum, Judaeum Slicet (Lead-glass, that is, of the Jews)

- The Jewish Glassmakers of Genoa

- The da Costa Family in the Diaspora

- Notes

Lead Glass Introduced into England

Litharge, the oxide of lead, when used in the manufacture of glass, renders the glass softer, more easily cut and faceted and enhances its brilliance.

Historians have long repeated that the formula for lead-glass was invented in 1674 by an Englishman, George Ravenscroft. Historians often make a habit of being in error. In this case the error could not be more gross. Ravenscroft was neither an artisan nor an inventor. It is true that Ravenscroft patented the process; it is false that he invented it.

Ravenscroft was the son of a prosperous English ship-owner who traded with Venice, and glassware was a significant part of that trade. England had long been desirous of developing its own glass industry and divorcing itself from dependence on imports. Attempts to lure Venetian masters to England were frustrated. The Venetians were so jealous of their art, that assassins are known to have been sent out after glassmakers who sought their fortune abroad. Even a Duke of Venice, while he was still serving as ambassador to France and before he ascended to an exalted position as the Doge of Venice, was commissioned to carry out such a mission, and he did.

Ravenscroft was engaged in 1673 by the Glass Sellers Company to advance research on glassmaking in England. He succeeded in hiring Italian glassmakers from Altare, the main glassmaking rivals to the Venetians. The Altarese were descendants of glassmakers brought in by the crusading Marquise de Montferrato from Eretz Israel, the Holy Land of Israel, to his fief in Piedmont, Italy.1 In contrast with the Venetians, the Altarese glassmaking community, known as the Università d'Altare, encouraged the emigration of their masters. The movement from the community into the Diaspora reached sizable pro-portions after new statutes were imposed on the community in 1512. The glassmakers were tied to Christian rites and rules, and a patron saint was appointed to "protect" them. Nonetheless, Sephardic glassmakers were welcomed into the community during this period. Many remained and became integrated into the community. Altare served other Sephardim as a way-station into the Diaspora.

Outstanding among these Sephardim was Giacomo da Costa. The da Costas were not among the twelfth century glassmakers who had been brought in from Palestine by the Marquise. They were among those who

had left Spain and were made welcome by the glassmakers of the Università d'Altare. The da Costa family became prominent in that host community. During the period when England was seeking to develop a glassmaking industry no less than three of the five ruling council members of the Università d'Altare were da Costas.

There can be little doubt that it was Giacomo da Costa, who brought to England the ancient knowledge of the use of the oxide of lead for the production of crystal glass.

Altare was then under the reign of the Gonzagas of Mantua. The hegemony of the Gonzagas extended at this time into Provence, and there was an intense movement to and from that area by the Altarese. Many glass manufactories were established in various cities of Provence during that period. The Altarese da Costas are known to have established themselves in a worthy fashion in Provence and some of them went up into the Netherlands. It was indeed from the Netherlands that Giacomo da Costa of Altare was evidently brought to England in the 1660's to join other members of the family who were already established in England, and had come from Antwerp.

In 1658 a Giuseppe (Joseph) da Costa was listed among the unemployed of Altare. His name appears among a large number of lesser skilled glassworkers and not among the 33 Maestri then listed as being out of work. In contrast with the unskilled Giuseppe, various highly skilled da Costas left Altare at that economically depressed period. They show up at various European locations. A gaffer (glassblower) called da Costa is known to have worked at Henley (1675), [who] belonged to an Altarist family."2 Altare was likewise represented at Ninwegen by Battista da Costa between 1660-70.3 Still another da Costa returned to Portugal to erect a factory in Lisbon in the latter quarter of the seventeenth century.4

Lest any doubt remains concerning the fact that George Ravenscroft obtained the formula for lead crystal from Giacomo da Costa, we turn to an English eye-witness account of the time. In April of 1676, but two years after Ravenscroft obtained a patent for the lead-glass formula, a Dr. Robert Plot was investigating the natural history of Oxfordshire. Dr. Plot was a distinguished scientist, a Fellow of the Royal Society and an Oxford Don. In the course of his research, Dr. Plot visited and studied the Ravenscroft glasshouse. Dr. Plot listed its processes as "the invention of making glasses of stones or other materials at Henley-on-Thames lately brought to England by Seignior da Costa a Monferates (sic) and carried on by one Mr. Ravenscroft who has gotten a patent for the sole making of them."

The Dagnia Family

Glassmakers from the same glassmaking community, and likewise a Sephardic family, the Dagnias, introduced the use of lead ("flint") glass into Scotland. Altare was then under the rule of the Duke of Mantua, who had privileged two Dagnias brothers with a patente di familiare, a special privilege that gave them the run of the palace. These privileges were granted to favorite Jews who were counselors of the court or rendered other services."The Dukes availed themselves of the services of Jewish doctors, engineers, and of course, bankers. With some of the latter the dukes maintained special relations, elevating them to the status of familiari, or members of the ducal household,; and granting them special privileges, unusual even for the comparative (though selective) liberalism shown by the Princes of the Renaissance toward some of their Jewish subjects."5

The earliest known Italian allusions to the family appear on the Ligurian coast at Savona, the port that served Altare. The records of the port of Savona register the purchase of soda, a vital ingredient in the process of glassmaking, by Guglielmo Dagna in 1480 and a shipment of a load of glassware to Nice by the same gentleman as early as 1487.5 The Spanish origin of the name is revealed by its spelling, the soft gna of the Spanish language not yet having been transcribed into the equivalent gnia of Italian. The name, Sebastiano Dagna, still marked with its Spanish form and tone, appears on a notarized invoice dated 1554.7

Some Dagnias moved to Parma. A Benedetto Dagne was registered as a vetraio (glassmaker) of Nevers in 1559. In 1602 an Oduardo Dagna is recorded as a consular member of the Università d'Altare, apparently the very Duardo Dagna who was given the patente di familiare by the Gonzaga duke seventeen years later in 1619.

Other Dagnias moved to Provence after the area came under the hegemony of the Gonzagas. Then, about 1630, Oduardo Dagnia and his four sons, Onesepheris, Jeremiah, Eduardo, and Giovanni and their families sailed to England. That the family should have moved to England so soon after it had gained the prestige and privileges of the Ducal patente reflects the depressed state of the glassmaking industry in Altare at that time, and the long-standing desire of the Sephardim to seek opportunity and a permanent home.

In England they became deservedly renowned for their industriousness and for their contributions to the advance of the art and industry of glassmaking in England. They were enticed there by Sir Robert Mansell, an erstwhile English vice-admiral who was not content to rest on his laurels after retiring from the English navy. The English glass historian, W. A. Thorpe, described Sir Robert as a "Welshman with the manners of an admiral and the brains of a financier."8 Sir Robert was enamored with the art of glassmaking and enthusiastic about its potential as an Eng-lish industry. His zealousness made it hard for King James I to understand why "Robert Mansell, being a seaman, whereby he got so much honor, should fall from water to tamper with fire, which are two contrary elements."9

In recognition of the brilliant campaign Admiral Mansell had conducted against the pirates of Algiers, he was rewarded with special privileges. In 1615, a year in which the burning of wood was prohibited to the smiths and glassmakers, Sir Robert obtained a monopoly on the use of coal as a substitute fuel in the production of glass. Mansell went to Italy to seek masters capable of revitalizing the glassmaking industry in England. Among those he interested in emigrating were members of two glassmaking families who had won a place at the court of the Duke Fernando of Montferrato, the Perrottis and the Dagnias. Both families subsequently became justly celebrated for their seminal role in the development of the glassmaking industry in France and England.

Soon after Sir Robert Mansell's patent expired, the Dagnias struck out on their own. One branch of the family, headed by Onesepheris and Jeremiah, established the first glasshouse in Bristol in 1651.10 In Bristol, Eduardo met Dud Dudley, a master iron-monger whose father obtained the monopoly for smelting iron with pit-coal in 1620, and passed on the patent to Dudley in 1638. Another company near Stourbridge obtained the rights to the patent in 1670. Their desperate attempt to put the process into operation was a dismal failure. Their iron pots continued to crack.

Glassmaking had already been introduced into Stourbridge, but the Dagnias were responsible for the phenomenal growth and success of the industry. By 1696 the number of glasshouses firing up furnaces in the area burgeoned to a phenomenal 88, signifying that the industry had attained maturity and strength. Seventeen bustling glasshouses were functioning in Stourbridge alone. In 1709, Dudley, having been dubbed a Lord, and having become expert at fabricating durable crucibles, made a business of leasing "melting pots" to glassmakers. The method of payment was unique. Among his charges was "125 quarts of top quality wine to be delivered to the Talbott Inn in Stourbridge."12

In the meantime, Onesepheris, together with Edward (formerly Eduardo), and John (formerly Giovanni), left the family behind in Stourbridge and struck out in 1684 to Newcastle-on-Thyme, Scotland, another area in which coal was readily available. They established glasshouses "for making white glass and bottles," founded the famous Closegate Glasshouse, and created the "Newcastle style." Closegate glassware became the standard for the English glassmaking industry. It is now prized by antique collectors around the world.

Not least among the glassmaking innovations made by the Dagnias in England and Scotland was the use of lead oxide to produce "flint glassware" and the development of the technique of "cut crystal" to a high artistic level.

Vitreum Plumbum, Judaeum Slicet (Lead-glass, that is, of the Jews)

The Da Costas and the Dagnias were the inheritors of a knowledge that extended back 3000 years. The art of glassmaking was born in Akkadia and grew to its maturity on the Levantine coast of the Mediterranean, from whence both the art and the artisans spread out into the world.13

The most ancient examples of manufactured glass date back to the 24th century B.C.E. Analyses of the earliest glass artifacts from Nuzi and elsewhere in Mesopotamia show that the oxide of lead was known and used in that ancient time. It was still being used in the Levant a thousand years later.

Lead glass, in fact, was conventionally known as vitri Ijudaici ("Jewish glass") during the Roman period. It continued to be so designated into the late Renaissance. The antiquity of the appellation is evident from the writings of as ancient an author as Heraclius, who provided us with the following formula:

A thousand years later the trading in lead compounds as well as the manufacture of glass was still being carried on in Fustat (Cairo). Documents of the 12th and 13th centuries recovered from the geniza (archive) of the ancient synagogue of Fustat record the activities of both the glassmakers and the dealers in lead oxide of that Jewish community. The mineral was used for medicinal purposes and was the prime ingredient in the cosmetic eye makeup of which the Egyptians were enamored, as well as for the manufacture of glass. So important was lead oxide that the dealing in it and processing of the mineral formed a distinct profession in the Near East.14

Lead glass was known through the 14th century as Vitreum Plumbum, Judaeum Slicet ("lead glass, that is, of the Jews).15 So persistent was the identification of the product with the Jews that as late as 1836 in Birmingham, England, lead glass was still, ironically, referred to as "Jewish glass" despite the patent granted to Ravenscroft more than a century earlier!16

The Venetians were also familiar with the use of lead oxide for producing a softer glass several centuries before the son of an English shipper patented the formula. At the end of the thirteenth century Antonio da Pisa of Murano left detailed instructions on the use of lead compounds for producing lattimo (milk glass). It was the first formula for what became a most important and profitable product for the Venetians. It provided Venice with an excellent, cheaper substitute for imported white china prized by the Europeans, and was a formula that every nation sought by fair means or foul to obtain.

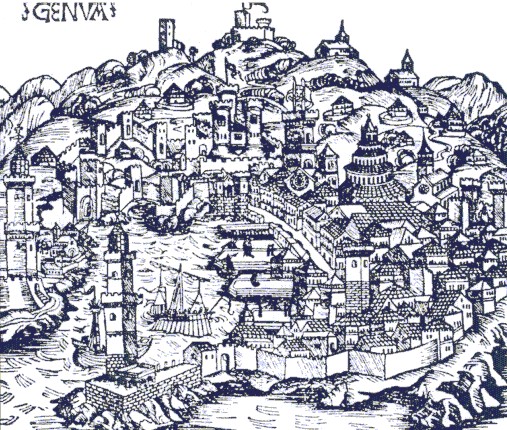

Why then, do historians persist in ascribing the invention of lead glass to Ravenscroft?The Jewish Glassmakers of Genoa

It should suffice that in 1674, just before Ravenscroft obtained the patent for lead glass, there lived in the ghetto of Genova a certain Abram Salom, whose trade was registered as "the processing of lead oxide for the purpose of glass manufacture."17 Thus it is learned through a series of census' taken of the residents of the Genovese ghetto that the processing of and the trading in lead oxide for the express purpose of producing lead glass was a duly recorded trade in Altare at the very time a royal patent was being granted to George Ravenscroft. A census taken that same year shows that a branch of each of the da Costa and Dagnia families were neighbors of the Saloms in the ghetto. The documents containing this registration and a score of other documents relating to the Jewish glassmakers of Genoa were uncovered by the author from the Archivio Segreto, or "secret archives" of Genoa. No other historian had previously delved into those files!

Abram Salom was among a group of Tuscan Jews who, a century after the Jews had been ignominiously expelled from Genoa, were welcomed back in 1659. The glassmakers among them were granted the exclusive right to produce glass and glassware of every kind within all the dominions of Genoa for a period of twenty-five years!

Such an extraordinary privilegio speaks volumes to those familiar with the vitric arts. It attests to how successfully the inheritors of the secrets of glassmaking had kept those secrets over three thousand years.

Two facts become clear from the terms of the privilegio:

1: No one in the Republic of Genoa possessed the knowledge and the ability to establish a viable glassmaking industry.

2: The Jewish glassmakers from Tuscany possessed that knowledge and ability, a discipline that had been passed down through many generations.

Jews throughout Christendom were barred at this time from practicing most crafts unless they converted, or feigned conversion to Christianity. The fact that the Genovese were obliged to turn to Jews to introduce the vitric industry within their dominions is significant evidence that despite the severe exclusionary restrictions that had been inflicted upon Jewish artisans for more than a millennium, the ancient relationship between the Jews and the art of glassmaking had endured.The art of glassmaking was not new to Genoa. Glassmakers had previously fired furnaces in the Republic. Genoa did not obtain glassmakers from the Near East as the Norman and the Piedmontese crusaders had done. At the end of the 13th century, before Genoa came under the domination of Spain, an early chronicler recorded that " the first glassmakers in Genoa came from Florence. In fact, the earliest identifiable Genovese glassmaker, Zino da Firenze, is registered on a document of 1281.8 From that time forward until the expulsion of Jews from Genoa, the influx from Florence (and later from Spain) was substantial. Guido Malandra, in his authoritative history of the Università d'Altare, lists an impressive number of these immigrants. Two of the glassmakers are specifically listed as conversi, Jews who had converted to Christianity:

"Compagno, conversi glassmaker of Florence."

October 13th, 1309:

"Benagio, conversi of Florence who is a qualified glassmaker."

As Genoa fell deeper under Spanish influence, the glassmaking industry faltered. The desperate attempts of the Genovese to maintain a viable industry led to the granting of a series of glassmaking mono-polies to foreign glassmakers. The practice first appears in 1410, in the records of a Cione di Lucio de Pisa.19

It is noteworthy that the practice of employing the names of towns as a surname was commonly, albeit not exclusively, a Jewish practice. Thus names like de Pisa or Pisano ("of Pisa"), et al, indicate a probable Judaic heritage. Again, on the 36th of May, 1432, two consoli of the city of Genoa registered an offer of Jacobo de Rapallo e Soci ("Jacob from Rapallo and his partners"), to establish a glassmaking facility in Genoa on condition that no one be permitted to import glass artifacts into the Republic "neither by sea of land" without a license of express permission would be granted by the said Jacob. Rapallo is an important seaport just south of Genoa. It is one of the way stations along the path from Tuscany to Genoa and eventually, in the sixteenth century, became one of the ports through which Spanish Jews escaped the attention of the Spanish Inquisitors.

In return for protection from outside competition, Jacob proclaimed that he would undertake to manufacture a great number of glass vessels, "enough to satisfy the whole world!"

Whether Jacob did not live up to his guarantee, or whether some other reason prevailed, only nine years later, in 1441, exclusive rights were again granted by the Republic of Genoa to a Laurentia Beca of the Università d'Altare. He was given the right to set up a glassmaking furnace in Genoa with the express condition that no other glassmakers would be allowed to operate in Genoa in competition with him. Four years later the exclusive right to the sale of glassware in Genoa was added to that of manufacture, a restriction that closed the market to imported glassware, particularly from Venice. 21

In 1567, the Republic, having become a virtual vassal of Spain, expelled the Jews at the behest of their Spanish overlords. It is significant that despite the successive granting of exclusive manufacturing rights to artisans, none stayed to establish a glassmaking industry, indicating that glassmaking did not take root in Genoa. After the Republic came under Spanish domination, and throughout the century in which the ban against Jewish residence remained in force, no other glassmaker appears in the Genovese records. The quality of Genovese glassware first deteriorated rapidly to "green" or "forest glass," evidently the products of a few ill-skilled workers. Soon the art disappeared from the Republic.

As the years passed, Genoa tried desperately to recapture the art. Their great rivals, the Venetians, were enjoying universal acclaim and commercial success for glassware. Glassware was still being produced in Spain, a regime that ostensibly had been a protector, partner, and ally of the Genovese. Only next door, just over the mountains that press Genoa against the sea, the glassmakers of Altare were not only producing glassware but spreading the art abroad.

Altare was separated from Genoa a mere fourteen kilometers. Again and again the Genovese attempted to entice Altarese glassmakers with special privileges to construct their fiery fornaci within the Republic. The Università d'Altare was suffering economically during this period. It would seem that the community should have welcomed work in neighboring Genoa. The Altarese glassmakers were, in fact, moving massively into Provence, Amsterdam, Antwerp, and eventually into England. It is evident, however, that so long as Genoa remained under Spanish domination, no temptation was sufficient to overcome the resistance of the Altarese to help themselves by accommodating their neighbor. The Altarese council specifically prohibited its glassmakers from working in the Spanish-dominated Genoa. Teeth were put into this prohibition by statutes passed in 1601. Severe sanctions were to be imposed upon any Altarese glassmaker who went to practice the art in Genoa.22

Glassware was being produced during this period by Altarese artisans in the mountains close behind Genoa at Masone, a village even nearer to that metropolis than Altare. The scoria of ancient glassmaking facilities found throughout the thick forests surrounding that picturesque mountain-top village suggests that such manufacture was indeed surreptitiously taking place under the very noses of the Genovese hierarchy. It appears that glassmakers from the Università d'Altare ranged afield from the Piedmontese fief of the Marquisate de Monferrato into the Ligurian hinterlands of the Genovese Republic to take advantage of the hardwoods foresting the mountain around Masone.

The peculiar circumstances of this activity is that Masone was then ostensibly under Genovese hegemony, yet none of the glassware made its way directly into Genoa! The Altarese marketed their glassware overseas through Savona, a port nest door to and competitive with Genoa.

The Genovese were obliged to humiliate themselves by purchasing massive lenses for a new lighthouse from the Altarese artisans of the Università .

For a hundred years both Jews and glassmaking were absent from Genoa. The art reappeared with the arrival of the Jews in 1659.

Spanish treachery against the interests of their Genovese protectorate disenchanted the ruling hierarchy of the Republic. The Republic was in dire need of economic and technological stimulation. Genoa's economy was further devastated by a rampant plague. Frustrated by Spanish restrictions on its development and disillusioned with dependence on Spain's good will, the Genovese cut loose from their Spanish overlords. Then, as was common in those days, the Genovese turned to the Jews for industrial and economic assistance.

Recognizing a new opportunity for entering into the commercial affairs of a most important port, a certain Salamon d'Italia petitioned the directors of the Banco San Giorgio in the year 1655 on behalf of a group of Jews from Tuscany for the right to settle and conduct business in the Republic of Genoa. Salamon was a resident of Mantua, but was at that time in Casale Monferrato. Casale was then under the dynastic rule of the Gonzagas, as was the Università d'Altare. The Banco San Giorgio was an official and powerful branch of the government that acted as a sort of ministry of finance for the external commercial affairs of the Republic. It was locally referred to as the Marinino, reflecting its interest in maritime affairs.

The meeting led to the issuance of the first Statuti di Tollerenza ("Statutes of Tolerance"), but they were shortly denounced. Evidently, despite the enticing prospect of Judaic assistance in developing local industry and international commerce, the residue of Spanish influence still lingered through the church. Continued economic torpidity, and further friction between the Genovese nobility and their Spanish mentors served to reopen the issue. In 1658 two Jewish champions of a group of Tuscan Jews, Abram da Costa and Aron de Tovar, renewed negotiations with the Banco San Giorgio. They succeeded in obtaining the new Capitoli per lo Nazione Hebrei, statutes that provided favorable terms for the Jews to "come and settle in the Serenissima Republica di Genova." The statutes became effective in April, 1659. Jews then returned to the Republic from which they had been expelled a century earlier.23

The thirty pages of the decree granted the immigrants such compre-hensive rights, privileges, and protection, and were caged in such warmly welcoming terms that they can be construed as constituting a sort of apology for having expelled the Jews in the first place. "We grant to that nation first of all salvocondotto (security and freedom of movement), for their persons and property," the statutes cordially begins,

We are left to speculate under what circumstances Abram da Costa and evidently a few other Jews were able to reside in the "area" before an official sanction for residence was granted. The phrasing of the statute leaves the impression that negotiations were ongoing since the renunciation of the original invitation three years earlier. A reasonable inference would be that Altare was the "in the area' referred to.

Bringing in a Jewish community constituted a victory for the Genovese secular, commercial interests in alliance with the nobility over the Spanish-controlled church hierarchy. The Jews were considered necessary for shedding Spanish shackles on the expansion of Genovese production and trade.

Our curiosity is further piqued by a document issued only a few months later, soon after the first wave of Jewish immigrants into Genoa had settled into the newly-constituted Genovese ghetto. A special license was issued to three un-named Jews to carry "whatever kind of arms, other than the kind of arms generally prohibited, they needed to protect themselves wherever in the dominion they may find themselves.25 The unusual fact that names are not given in this official document (they are simply designated as "three Jews"), suggests that the choice of the three would be left to the Jewish community.

Glassmakers were included in the very first group of Jewish immigrants. They forthwith formed a cooperative, and were immediately granted the "exclusive rights to produce or have produced glass and glassware (cristalli) of every kind." The monopoly was not confined to the city of Genoa, nor to the province alone but was extended to "all the dominions of the Serenissima Republica de Genova."

The document setting forth this inclusive privilegio begins with a statement that attests to the fact that the production of glass was then absent from all of Genoa, for it calls for the introduction of the art by the Jewish immigrants. "Eliahu Bernol, together with his Jewish companions," the decree begins:

"...have requested that the Republic of Genoa grant the privilege of introducing the production of glass and glassware into the Republic of Genoa, and then to continue production for a period of 25 years in this city or elsewhere in its dominions, with [the understanding that] such production will be prohibited to anyone else, with the promise that they will introduce such facilities within the space of one year and actively maintain production through the said period of 25 years."26

The da Costa Family in the Diaspora

A branch of the family of Abram da Costa de León, one of the two Jews who had secured the right of Jews to resettle in Genoa was well represented in Altare. An extraordinary number of da Costas became consular members of the Università d'Altare soon after their integration into the community. No less than three out of the five consoli in the year 1645 were members of this distinguished family. The other two council members were a Ponte and a Rachetti, likewise Sephardim. The fact that all five of the designated officials of the community were from Spain at this time indicates that a warm welcome was extended to the glassmaking Spanish Jews. This circumstance is of vital significance inasmuch as the community had stringent statutes against allowing stranieri ("strangers" or "foreigners") to work at the furnace. Even the local Paesani were prohibited from learning any of the secrets, let alone given permission to apprentice at the trade. The glassmaking community and the local population remained separate throughout the eight centuries of coexistence. It is indeed remarkable that not one Romeo and Juliet story made its way into the Università's folklore over so many centuries.It is clear that the Sephardic emigres were not looked upon as strangers or foreigners but as family. Glassmaking was considered a noble art and those that practiced it were given quasi-noble status by the actual noble rulers of both Italy and France. The names of the five consoli of the Università are provided by an 1895 French transliteration of an Altarese document of 1645:

We can assume that Abram da Costa de León was related to the da Costas of Altare, albeit no documents have been found that make the connection definitive. All these da Costas, however, were members of a remarkable and most illustrious family whose odyssey through the western world is a saga in which truth is stranger than fiction.

Da Costas were among the Jews who fled from Spain into Portugal during the series of repressions from the 13th century forward. The addition of "de León" to the surname of Abram da Costa identifies the Spanish region from which the family stemmed, as it does to the name of the famous Spanish explorer Ponce de León. The kingdom of Castilla y León was a region of early Christian Spain that was intensely populated by Jews.

The exodus of the da Costas from Iberia was spurred by incidents such as that which occurred the day Lisbon awoke to find church doors plastered with placards blaring forth the blasphemous message: "The Messiah has not yet come. Jesus is not the true Messiah!"

A Maranno, Manuel da Costa, was accused of the heinous act. He was arrested, tortured cruelly until he confessed his guilt. Then, with the sophisticated methods developed over a century of producing excruciating torture, Manuel was slowly and methodically agonized to death.

Abram da Costa de León stayed behind in Genoa to continue his activity as consul of the Università Ebraica de Genova. Abram petitioned the Serenissima Signori della Republica de Genova as follows:

The granting of the request is eloquent testimony to the reputation of the Jews for stimulating economic growth, and for the rationale behind their remarkable survival.

The paths through the Diaspora intertwine tortuously. The progenitors of the Dagnias and the da Costas and all their fellow glassmakers passed along these paths and finally forgot who they were and from whence they had come.

Two of these wandering families brought the secret of making lead glass into England and Scotland.

Notes

- HHF Fact Paper 25. The Glassmakers of Altare.

- W. A. Thorpe, English Glass, London, 1935, 156.

- F. W. Hudig, Das Glas, 1925, 71.

- Alice Worthington Framington, Hispanic Glass, 117,

- Simonsohn, xviii, xxvi.

- Guido Malandra, I Vetrai de Altare, Savona, 1983, 242, 250.

- Malandra, Ibid., 252.

- Thorpe, Ibid., 115.

- Eleanor S. Godfrey, The Development of English Glassmaking, 1560-1640, Un. Of Carolina Press, 1975, 16.

- Harold Newman, An Illustrated Dictionary of Glass, London, 1977, 87,

- D, R. Guttery, From Broadglass to Cut Crystal, London, 1956, 77-78.

- Guttery, Idem.

- Samuel Kurinsky, The Glassmakers, An Odyssey of the Jews, Hippocrene Books, 1991.

- S.D. Goitein, A Mediterranean Society, !971, Vol. !, 109.

- Antone Gasperreto, Il Vetro di Murano dalle origine ad oggi, 1958, 32.

- I. A. Knowles, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 1914, LXII, 570.

- Archivio Statale di Genova, (hereafter ASG) 1390. Abram Salom, his wife and nephew are recorded in several census's of the Genovese ghetto. His trade is explicitly defined "Fa mestiere di tirare piombi per it vetro."

- Guido Malandra, Ibid., 36.

- L.T. Belgrano, "Cartario genovese ed illustrazione del Registro archivescovile," Atti Soc. Lig. Storia Patria, II, 1870, 51. Malandra, Ibid., 152.

- ASG, Arte (Ars Vitreorum 1432, The request was made by the consuls, Lucca de Rappalo and Francesco Magerre.

- ASG Ars Vitreorum, 1441.

- Manilio Caregari and Diego Moreno, "Maniffatura vetraria in Liguria tra XIV e XVII secolo," Archeologia Medievale II, Centro per lo Storia della Tecnica, Genoa, 1975.

- ASG, Ars Vitreorum, Capitoli per la nazione Hebrei, June 16, 1658.

- ASG, Hebreorum, Idem.

- ASG, Hebreorum, File no. 44, July 3, 1659.

- ASG, Hebreorum, File no. 1390, August 12, 1659

- ASG, Hebreorum

- ASG, Artium, document dated July 24th 1673.

- Abbe Boutelier, Le Verrerie et les gentilshommes verrieres de Nevers, 1895, 22.

- Abbe Boutelier, Idem.