Egypt and the Semites Part II: The Second Intermediate Period

Fact Paper 10-II

© Samuel Kurinsky, all rights reserved

- Egyptian Progress to Stagnation

- Manetho and Egyptian History

- The Second Intermediate Period

- The Bahr Youseff, Joseph's Canal

- Aamu Technology and Culture

- The Adulteration of History

- Notes

Egyptian Progress to Stagnation

Immigrants from southwest Asia with Semitic characteristics established villages in the Nile Delta and Fayoum regions of Lower (northern) Egypt from 5500 to 3100 B.C.E., as was seen in Fact Paper 10-I. They introduced husbandry and agronomy, the twin foundations of civilization, as evidenced by the wide variety of Asiatic plants and animals raised in their settlements The agricultural tools employed by these villagers and the other technological and cultural attributes they possessed contrasted sharply with the hunter-gatherer culture of the indigenous Stone-Age populations of Egypt of the period.

As F. Wendorf pointed out, this new population of Asiatic peoples instituted a cultural foundation in Lower Egypt on which all subsequent Egyptian civilization was based.1

The inhabitants of Upper (up-river or southern) Egypt began to absorb some of the Asiatic agronomic and technological attributes from the Semitic traders passing by up the Nile on their way to Nubia. This traffic became frequent at the end of the Predynastic period (Gerzean Period, 3500 to 3170 B.C.E.). As a result, the Egyptians began to emerge from the Stone Age into the Chalcolithic (Copper-Stone) Age. Irrigation began to be employed, enabling the arid region to sustain a larger population than had heretofore been possible.

Egyptian overlords ensconced in enclaves along the Nile also benefitted from the imposition of tribute. As Nile traffic increased, as agricultural areas widened, and as the population burgeoned, a new Egyptian social order arose, in which power was wielded by an ever-growing hierarchy. As overlords gained power, they took to raiding each other.

One such warlord attained the right to wear the "White Crown" of Upper Egypt, that is, to rule over all of Upper Egypt. Eventually he became powerful enough to raid and conquer Lower Egypt. He donned the symbol of this conquest by donning the "Red Crown" of Lower Egypt and commemorated the event on the so-called "Narmer Palette."

There were probably many raiders of the northern villages, such as the Scorpion of legend, or the Narmer of the Palette, or Menes (the first king of the First Egyptian Dynasty). That these characters may have been one and the same is open for debate. According to Egyptian lore, however, the "unification" of Egypt took place under Menes.

For a period of twelve hundred years, from Menes, c.3100 B.C.E. to the twelfth Dynasty, c. 1900 B.C.E., Egypt's resources were committed to the centralization of power, to the deification of successive kings and to their glorification and that of their underlings. Great monuments were erected, great statues were carved, great palaces and elaborate tombs were filled with exquisite art and artifacts. The Egyptian populace was taxed to the limit to maintain hordes of slaves, and freemen were subjected to indenture during agricultural off seasons. Under oligarchical rule, however, creativity was stifled. Egypt remained mired in the Chalcolithic Age while Southwest Asia passed on from the Early to the Middle Bronze Age.

The rich accouterments of early dynasty tombs persuaded historians that a period of prosperity had ensued. How easily does royal gold blind ostensibly sensible scientists to the facts! The luxury wares from royal tombs enhance museum halls and leave the impression that such opulence reflects a glorious condition of Egyptian society. The mirage is persistent, despite the fact that it is clear that far from being a period of progress and prosperity, the welfare of Egypt and the evolution of technology were being adversely affected.

The centralization of power and the monopolization of trade by the Egyptian hierarchy had a such a deleterious effect upon progress that virtual stagnation ensued.

Intermittent periods of aggression and peace ensued for the next twelve hundred years. During peaceful intervals, the Semitic peoples of Lower Canaan flowed into the Delta region. These periods mark whatever advances in culture and technology ensued. During the twelfth Dynasty (roughly 2000-1800 B.C.E.), such a peaceful period developed.

An important Egyptian text, "The Tale of Sinuhe," is a lengthy account that illustrates the positive nature of the intercourse between Egyptians and Canaanites of the times. It took place during such a peaceful period in the reign of king Sen-Usert I (1971-1928 B.C.E.). It relates how the said Sinuhe, an Egyptian official of high rank, having fallen afoul of the law, fled to Retenu ("Canaan"). Hiding in bushes and creeping through fields by day, he slipped by the Egyptian frontier guards by night, only to suffer hunger and thirst in the Sinai desert.

"I was parched and my throat was dusty. I said, 'This is the taste of death!'"

Just then Sinuhe heard the lowing of cattle and came upon beasts being herded by Canaanites, headed by a kindly chief "who had been in Egypt." The well- traveled Aamu ("Semite") rescued Sinuhe, reviving the thirsty and famished fugitive with water and boiled milk. "What they did for me was good," thankfully recorded Sinuhe.

Sinuhe resided a year and a half in Canaan. A certain chieftain of Upper Canaan, Ammi-shen, impressed with Sinuhe's reputation and character as given him by Egyptian members of the Canaanite's court, offered to take him into his service to teach his children - presumably the Egyptian language.

"Thou wilt do well with me, and thou will hear the speech of Egypt," the Canaanite chieftain told Sinuhe, referring to other Egyptians in his service. Sinuhe was treated as one of the family, which he eventually became by marrying the chieftain's daughter. He was set up by the chieftain in style with his own estate, prospered, and in the rendition of his experiences, describes the land of Canaan.

Sinuhe's description of Canaan is startlingly similar to the biblical description of the "Promised Land." "Figs were in it," Sinuhe wrote, "and grapes. It had more wine than water. Plentiful was its honey, abundant its olives. Every [kind of] fruit was on its trees. Barley was there, and emmer. There was no limit of cattle."

The positive relationship between the Canaanites and Egyptians of the period is likewise illustrated by the biblical story of Abraham. The parallel account is clearly a tribal memory of a propitious time in which, when drought afflicted Canaan, Canaanites were welcome to forage their animals in Goshen, the fertile region of the Nile Delta. Abraham's sojourn in Goshen would have taken place shortly after Sinuhe returned to Egypt.

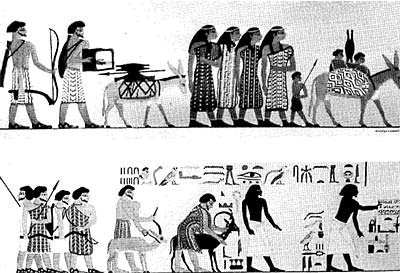

By the nineteenth century B.C.E., commercial traffic up the Nile had become a great boon to the nomarchs of Upper Egypt, who not only traded with the passing entrepreneurs but profited from "customs" collected from them on their way to Nubia. One such prosperous baron, named Knumhotpe, had a forty-foot-long mural painted in his tomb at Beni Hassan, about halfway up the Nile to Nubia. By commemorating the lucrative trade in his final resting place Knumhotpe sought to assure an eternal traffic of tradesmen paying tribute to him in the afterworld.

The painting evidently registers an actual event which Knumhotpe felt worthy of eternal repetition.. It depicts a group of thirty-seven Semites in full size in the act of paying customs duties to the nomarch's officials. A bold hieroglyphic text states that these Asiatics are supplying him with such important items as stibium, a mineral required for eye makeup acquired in Mesopotamia. Knumhotpe evidently feared that the place he would occupy in the hereafter might lack the mineral, as was the case in Egypt. The date given is the fourth year of Sinusert II's rule, or about 1892 B.C.E.

The leader of the caravan of tradesmen and artisans is named Abushei, a distinctly Hebrew name. It was, for example, the name of a top general under King David. The leader is termed a Hy-khase, i.e., a "foreign chieftain from the hill country (Canaan)." The term "Hyk-Khase" was corrupted to "Hyksos," and, as we shall see below, it was under the rule of the Hyksos chieftains such as Abushei that Egypt made its most dramatic technological and cultural leap.

What is most remarkable about the rendering was the depiction of advanced tools and instruments as yet foreign to Egypt, implements that were not acquired by the Egyptians until the rule of the Hyksos!

Middle Bronze Age metal-smithing is one of the crafts practiced by the Abushei group, readily deduced from an anvil and a bellows loaded on the backs of the donkeys. An Egyptian artist thus presents evidence of metalworking technology that had not yet been employed by Egyptians.

Curvilinear, laminated bows are being carried by members of the troupe. At the time, the bows of Egyptian soldiers were made of simple arched twigs.

A 12-string harp or lyre borne by another member would likewise be unknown to Egypt until new forms of music, games and dance were introduced under Hyksos rule in the Second Intermediate Period.

Most striking in the great expanse of the mural were intricately woven fabrics of the clothes worn by both the men and the women. They were produced on an upright loom, another mechanism as yet unknown in Egypt, as were the vivid colors of the dyes employed, colors faithfully reproduced by the anonymous painter of the mural.

All these and many other Asiatic revolutionary cultural and technological innovations were soon to be implanted in Egypt under a succession of six Hyksos kings during whose reign Egypt was propelled into the Bronze Age. Unfortunately, the record of the most progressive period of ancient Egyptian history was compromised by three factors:

The succeeding Egyptian "Warrior Pharaohs" of the Eighteenth Dynasty ruthlessly ravaged every trace of the presence of the Canaanite kings. They almost succeeded in obliterating two centuries of Egyptian history.

Our knowledge of the events of the early Dynastic periods is skewed because it derives in great measure from the writings of Manetho (323-245 B.C.E.), a highly prejudiced source. Manetho was an Egyptian who rose to become the High Priest of the cult of Serapis at Heliopolis during the reign of Ptolemy II (283-246 B.C.E..

Manetho's version of Egyptian history, taken from inscriptions that the ravagers left to justify their actions, became the standard by which that history is written! His system of dynastic succession was perpetuated by archaeologists despite the fact that it has long been proven to be inaccurate, misleading and prejudicial.

Manetho and Egyptian History

Manetho wrote on Egyptian history during turbulent times in which the Jews were making a profound impact upon Ptolemaic society. A massive immigration of Jews began to tale place under Ptolemy I, swelling the numbers of Semites who traditionally inhabited the Nile Delta. Ptolemy II freed Jewish slaves upon his ascension to the throne and decreed privileges to the literate, technologically proficient Jews that were denied to the illiterate, unskilled Egyptian masses. Jews, including the former Jewish slaves, were placed in a social class above that of the Egyptians.

The humbling Ptolemaic statutes were undoubtedly among the causes of the festering hate that Manetho, who has been dubbed "The First Anti-Semite," bore toward the Jews. As an Egyptian he resented the demeaned status of the Egyptians. In this he identified with the Upper Egyptian barons who had rebelled fourteen hundred years earlier against the "Hyksos" whom Manetho identified as the forefathers of the Jews. Manetho repeated the slanders that the baronial conquerors employed to justify their overthrow of Semitic rule. Manetho embellished them with new anti-Semitic scuttlebutt.

History has not yet out-lived Manetho's virulent misrepresentations. They live on in contemporary historical and archaeological lore. For a long time archaeologists and historians repeated the self-serving records the "Warrior Pharaohs" had incised upon monuments to their glory as historical facts. Some even accepted Manetho's embellishments of the ancient inscriptions. The cycle thus completed became established Egyptian historiography.

Not a scrap of Manetho's manuscripts has survived. It is only from quotations from them that we obtain a portion of his history. Manetho was quoted in the first half of the first century by Apion, a politically influential Greek writer, likewise of Egyptian origin, who had gained fame as a Homeric scholar and author of his own work on Egyptian history. When charges were brought against the Alexandrian Jews, it was Apion who represented the Greeks before the Emperor Gaius. The Jewish philosopher Philo represented the Jews.2

Apion penned a poisonous polemic against the Jews, drawing much of his information from Manetho's no less biased account. Apion repeated Manetho's most spurious misrepresentations, as, for example, the patently fraudulent statements that Jews were expelled from Egypt as lepers, and that the Jews worship a golden ass that is enshrined in the Holy of Holies in their Jerusalem Temple.

Josephus penned a powerful defense of the Jews and Judaism, Contra Apionem, in outrage against Apion's extraction of the most blatantly false of Manetho's allusions to support his arguments. Josephus was particularly piqued with Apion's repetition as fact of absurd accusations, which Manetho himself had alluded to as rumor. In his dissertation Josephus used Manetho's own words against Apion, arguing that even as unsavory an anti-Semite as Manetho had conceded the antiquity of the Jews and inadvertently recorded positive aspects of a period in which their progenitors, the Hyksos, ruled Egypt.

The proposition that Manetho identified the "Hyksos," as progenitors of the Jews was assumed by all quoters from his work, including anti-Semitic Christian writers who had access to Manetho's writings before they disappeared. They used Manetho's calumnies to reinforce polemics against the Jews.

The remarkable fact is that the quotations are so brimful of contradictions that they serve to prove the opposite of what was intended! Together with inscriptions of the Egyptians who had overthrown the last Hyksos king, and with the surviving archaeological record, a remarkable picture emerges of a benign and beneficial reign over Egypt by the Hyksos over a period of almost two centuries.

Manetho is quoted by Josephus as saying that "the Hyksos were men of ignoble birth out of eastern parts, [who] had boldness enough to make an expedition into our country, and with ease subdued it by force, yet without our hazarding a battle with them." The force that overwhelmed Egypt consisted of 240,000 men who "burned our cities ruthlessly, razed to the ground the temples of our Gods, and treated all the natives with cruel hostility, massacring... and so forth." The contradiction of no resistance, yet massive destruction, like many other of Manetho's contradictions pointed out by Josephus, is obvious.

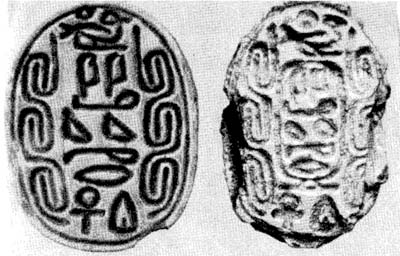

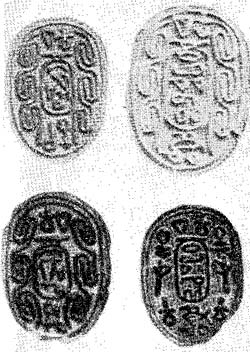

Archaeological evidence likewise draws a different picture of events. It is clear that a peaceful infiltration of Semitic peoples of Lower Egypt took place over centuries, and that by the time of Hyksos rule, scores of their villages were in existence. Hundreds of scarabs and seals of the heads of these villages have been unearthed. They bear mute testimony to that fact, as do several surviving lists of "kings" (that is chieftains) of the period bearing Semitic names. The villages headed by these chieftains functioned autonomously. As Manetho and the future warrior pharaohs who overthrew

Hyksos rule all stated, these chieftains "appointed" one of their own to become the chief-of-chiefs, the Hyksos who then assumed rule over all Egypt and Canaan, evidently with Egyptian consent.

The truth begins with the correction of an error in the translation of the phrase Hyk-Khase. The condensed version "Hyksos" is taken to refer to an entire race, and is thus blithely employed by historians. The word has been translated variously as "sand-dwellers'" "desert raiders," "barbarians," "bedouin invaders," and "desert despoilers." The myth of a mysterious invading horde of unknown race who came from an unknown area and disappeared just as mysteriously was born. The myth was promulgated throughout the corpus of scientific literature with scarcely a critical murmur to be heard.

Until, that is, that Sir Alan Gardiner came along. Gardiner, whose philological expertise and archaeological scholarship deserves the high respect accorded to it, pointedly took Egyptologists to task. "The word Hyksos undoubtedly derives from the expression Hyk-Khase, 'chieftain of a foreign hill country'... It is important to observe, however, that the term refers to the rulers alone, and not, as Josephus thought, to the entire race."3

"The invasion of the Delta by a specific new race is not out of the question." continues Gardiner... Some, if not most of these Palestinians were Semites. Scarabs of the period mention chieftains with names like "Anat-her'" and Yacob-her'" and whatever the meaning of her, "Anat was a well-known Semitic goddess, and it is difficult to reject the accepted view that the patriarch Jacob is commemorated in the other name.4

The term that the Egyptians employed for the peoples who came into Egypt from beyond the Sinai was Aamu. The term had earlier appeared as the designation for Southwest Asiatic captives and hirelings residing in Egypt as servants.5

Aamu has a marked similarity to the Akkadian word Amurru. Significantly, the Akkadian Amurru means "westerner," referring to the Semitic people to the west, whereas the Egyptian word Aamu means "right hand," or "East"! From the Egyptian point of view the Aamu were from the east and are clearly none other than the Amurru.

It will be recalled that the ancestral home of the Jews is biblically identified as Aram-Naharaim, the town in which Abraham's relatives dwelt, in which his father Terach and brother Nahor returned and stayed while Abraham and his entourage went on to Canaan. It is also the native town of the mothers of the Jewish people, Rebecca, Leah and Rachel. They were Amurru by Akkadian definition, and Aamu by Egyptian definition.

Aramaic, the ancestral language of the tribe of Abraham, become the lingua franca of international discourse during the Hyksos period.

Manetho unmistakably identified the Hyksos as progenitors of the Jews. First, he states that the Hyksos "built a great capital walled city Avaris, extending over an area of ten thousand acres from which successive "foreign kings" ruled for 511 years." The biblical reference to Avaris is thus confirmed.

Then, reporting on the exodus of the Aamus from Egypt, Manetho wrote: "They went away with their whole family and effects, not fewer in number than two hundred and forty thousand, and took their journey from Egypt, through the wilderness for Syria... They built a city in that country which is now called Judea, and that large enough to contain a great number of men, and called it Jerusalem.6

The parallels with the biblical account of the Exodus is obvious. How much more definitive can it get?

Manetho's fulminations are mindlessly repeated by most historians and their disciples. who promulgate and perpetuate Manetho's myth of cruel and massive invasion by the Hyksos. Cyril Aldred, instead, documents in his book, The Egyptians, how the infiltration of the Delta region of Southwest Asiatic peoples probably occurred:

"The story of Joseph reveals," writes Aldred, "how some of these Asiatics may have arrived... By the Thirteenth Dynasty the number of Asiatics, even in Upper Egypt, was considerable. The acted as cooks, brewers, seamstresses, vinedressers and the like. One official, for instance, had no fewer than fourty-five Asiatics in his household... It is not difficult to see that by the middle of the Thirteenth Dynasty the lively and industrious Semites could be in the same positions of responsibility in the Egyptian State as Greek freemen were in the government of Imperial Rome."7

"While to Manetho the seizure of power seemed an unmitigated disaster," adds Aldred, "we can recognize it as one of the great seminal influences in Egyptian civilization, rescuing it from political decline, bringing new ideas into the Nile Valley, and ensuring that Egypt played a full part in the development of the Bronze Age culture in the eastern Mediterranean."

The Second Intermediate Period

The Hyksos, or chieftains from hilly Canaan, erected no gigantic monuments, self-glorifying statuary and temples such as those that had drained Egypt of its resources of labor and material over many centuries, for there were none among them that claimed godly status. As Manetho sarcastically relates, the Hyksos kings were without divine attributes, for their king was no more than a chief-of-chiefs, appointed by the other chieftains to rule over them and over Egypt! The statement has two implications. That village chiefs enjoyed a great deal of autonomy, and that the accession to power of the six Hyksos rulers took place peacefully by election. The records show that they enjoyed among the most enduring reigns of Egyptian history!

The Hyksos recognized but one god, to whom they prayed at their capital at Avaris. He was named Sutekh, and he is depicted in clothes and a headdress that resembled that

of the Semitic god Baal8. .. Is it significant that Sutekh is also the name of the Egyptian God who slew Osiris?

Disappointed by the dearth of gargantuan statuary and elaborately furnished tombs and palaces, archaeologists and historians are led to declare that there was a cultural decline during this period. Museums petulantly concur for lack of imposing sculpture, mummies, mastabas and exotic statuary of beastly idols to embellish their halls.

Prestigious institutions allot little more than a plaque to the Second Intermediate Period, stating that during the two centuries of Hyksos rule, art declined. A note is sometimes added about the radical changes that took place during the most progressive period of Egyptian history.

The Hyksos sculpted neither great statues of themselves nor idols of fabulous gods. But the arts and expertise they infused into the fabric of the culture of Egypt were of a subtler nature, more durable than the stone of which the idols were carved, The innovations they wrought benefitted all Egyptians through all the generations to come.

What were those benefits?

The Bahr Youseff, Joseph's Canal

The greatest impact upon Egyptian economy and life was the engineering of an effective control of Egypt's water resources. Legends, both Judaic and Arabic, have it that Joseph, vizier to a late Pharaoh of the 12th Dynasty, Moeris, was responsible for this monumental and everlasting contribution to the welfare of Egypt. The legend has a factual foundation. Under Aamu rule such a vast project was indeed carried out.

Mesopotamian mathematics served in planning new systems of irrigation and in expanding the primitive systems previously installed in Egypt. The storage of water is as effective a hedge against periods of drought and famine as is the storage of grain, which we are told, was the first step recommended by Joseph to the Pharaoh.

We can imagine that it was a wise viceroy such as Joseph who spent years making a comprehensive study of the geodesy of Egypt. Finally a plan was formulated that transformed the land of Egypt forever. Two hard days journey from the river, resting within a ring of a range of rugged hills, lay the oasis known as el-Fayoum. It was cradled in a depression whose level lay below that of the Nile. On the verdant shores of a small, shimmering lake in the heart of this basin, a tribe lived cooly under the palms, unmindful of the unmerciful, encompassing wastelands.

A canal was dug. It was an ambitious undertaking, for the canal did not simply go directly to the Nile from the east, which would have been a massive project in itself. No, a much grander vision was launched. A canal was cut through the ridges bordering the Nile from afar in Upper Egypt and was furrowed northward through the hot sands a distance from but parallel to the Nile. A twin to the Nile was created, extending a full third of the Nile's Egyptian length. 5

The water of the great canal was fed to the flanking desert through a web of subsidiary canals. Finally it was diverted westward to expand the lake in low-lying el Fayoum and to create a second great lake, a reservoir that maintained the system through seasons of drought.

Whereas the Nile was hemmed in on the east by rugged cliffs that gave way here and there to a few paltry parcels of flat land, the web of feeder canals on the west fanned through the desert. The network of canals doubled the arable land of Egypt, hitherto almost entirely relegated to the delta. Upper Egypt became more than a mere passageway to Nubian ivory and gold, and was integrated into Egypt's economy, .

The legend claims that it was Joseph who named the great new reservoir "Lake Moeris," after the king for whom he was the viceroy. Zaccariah Sitchin a linguist and biblical scholar, reported that:

Arab historians not only attributed the project to Joseph but reported its circumstances. N It was, historians related, when Joseph was more than 100 but still held a high position in the Egyptian court. The other viziers and court officials, envying Joseph, persuaded the Pharaoh that to remain venerated Joseph should not rest on his laurels. He must prove again his abilities. When the Pharaoh agreed, the viziers suggested an impossible project - to convert the desert into a fertile area. "Inspired by God," Joseph confounded his detractors by succeeding. He dug feeder canals and created the vast artificial lake in 1000 days.9

The cold waters cascading from the mountains of Ethiopia and Nubia flowed warmed and welcomed through the hot desert. Joseph's task was fulfilled as the desert bloomed.

The legend was given credence by an American engineer, Francis Cope Whitehouse, who was retained by the British a century ago to resolve the problem of increasing arable land in the desert wastelands of Egypt, then under the hegemony of Great Britain.

Whitehouse was a distinguished technician, foresighted enough to have been an early inventor of devices to capture solar energy. In surveying the desert he was amazed to find that the problem of desert irrigation had been addressed more than three millennia ago. Whitehouse became intrigued with a small lake, the Birkut el-Qarun, or Lake Karoum, a freshwater lake in the midst of the vast Sahara desert, a lake that had no visible source! Piqued by this peculiar circumstance, Whitehouse began an investigation that led to his sincere conclusion that, indeed, the lake was a living legacy of a vast irrigation system created during the time of Joseph, viceroy to the Pharaoh Moeris.

Whitehouse mapped the ruins of ancient dams, ditches, and aqueducts, mute testimony to the prior existence of a sophisticated irrigation system. Ancient fish bones, shells and other signs scattered widely about and under the sands proved that the lake had been several times its current size, and that another lake had once existed.

Growing ever more intrigued, Whitehouse delved in archival records in Cairo and discovered that medieval maps of the el-Fayoum region showed two lakes in the region. Whitehouse's amazement continued to soar upon learning that the medieval maps were copies of maps drawn in Ptolemy's time. Whitehouse found references to an artificially created lake in the writings of Herodotus, Pliny, Diodotus, Strabo and Mutianus, and that the lakes were already ancient at their times. Herodotus wrote: "The water of the lake does not come out of the ground, which is here extremely dry, but is introduced by a canal from the Nile."10

Whitehouse found that the reservoir of two lakes had been debased by the Greeks The Greeks, ignorant of the hydrology of the system, attempted to increase acreage by reducing the extent of the lakes, and had instead caused large areas of rich soul to revert to dusty sand. Fertile fields relapsed into an arid landscape of sand, rock, and fish-bones.

Whitehouse followed the traces of a canal leading into the artificial lake and discovered that it was but tributary of a canal that paralleled the Nile for several hundred kilometers. The twin to the Nile is a canal that the Egyptians did not regard as an ordinary waterway but reverently referred to it as the Bahr Youseff, or "The Sea of Joseph."

Convinced that the solution to Egypt's water needs was the reconstruction of Joseph's magnificent project, Whitehouse fervently presented his proposal in April 1883 to the Khedivial Geographical Society in Cairo. In June he pressed his case before the Society of Biblical Archaeology in London, and thereafter in a series of lectures and pamphlets. He was ignored.

"Thus was forgotten the discovery of an engineer that some 3,500 years ago it was a Hebrew patriarch who had conceived, engineered and carried out the world's largest irrigation project until the TVA."11

Scientists finally came to appreciate the value of the ancient system and to recommend its reconstruction. Sir Alan Gardiner summarized the theory almost a century after its presentation by Whitehouse to a deaf parliament:

The original lake sank to below sea-level through the silting up of the channel until a king of Dynasty XII, by widening and deepening it, again brought the lake into equilibrium with the river. Thus was formed the famous lake of Moeris, which by functioning as a combined flood-escape and reservoir, not only protected the lands of Lower Egypt from the destructive effects of high floods, but also increased the supplies of water in the river after the flood season had passed.12

The entire irrigation system was reconstructed without crediting Whitehouse for his research.

A visitor to Egypt, if he would abjure the euphoria of viewing a mere mirage of Egypt from the deck of a floating hotel on the Nile, and would instead thread through the countryside west of the Nile, could not but be impressed by the multiplicity of farms and orchards being watered by the web of canals drawn from the Bahr Youseff. He would see groves of date palms alternating with green fields of grain, verdant vegetable patches, and wide expanses of white-capped cotton plants.

Whether the saga of Joseph is taken as true in whole or in part, one fact remains: Of all the wonders that the Aamu wrought for Egypt, none exceeds this great work for excellence, none testifies more eloquently to their genius, none bears better witness to their inspired accomplishments. Today, after more than three thousand years, the Bahr Youseff functions vigorously and converts more desolate desert into rich farmland than does the Aswan Dam. And - it performs its function benignly, unlike the dam, which increases the salinity of the soil as it is irrigated, a condition that portends ecological disaster.

The canal is, and has always been called in Egypt "The Bahr Youseff," which translates simply to "The Sea of Joseph." It is so designated on the maps of Mizraim, the land that we call Egypt.

Aamu Technology and Culture

The Aamu taught a people who had never known the wheel, nor bronze, nor the horse, nor the lyre. They brought these and more to a people who worshiped idols and prayed to beings with the heads of beasts and the beaked heads of birds.

During the tenure of the Hyksos chieftains Egypt leaped forward into a new era, advancing enormously in every field of knowledge and endeavor. The twelfth Dynasty Pharaohs had already employed Canaanite viziers to assist in the administration of affairs, the very process recalled in the Bible by the story of Joseph. Hundreds of scarabs bearing their names have been recovered from throughout Egypt. These and other evidences provide physical proof of the existence and function of such councilors to the subsequent Hyksos chiefs-of-chiefs, the elected rulers of all Egypt.

Wise men, encouraged by the benign conditions, came and settled into Lower Egypt. They taught astronomy, and medicine, and mathematics. The great mathematical Rhind papyrus, now in the British Museum, was then produced. The scroll contains 84 problems and their solutions. It is a copy made by the scribe, Ah'Mose, during the reign of the Hyksos king Apepi I. Ah'Mose modestly informed us that he copied the original, produced in the time of 12th Dynasty Amenemhet III, who reigned from 1842-1797 B.C.E., the very period in which Sinuhe was accommodated by the Canaanites, following which the patriarch Abraham found a welcome in Goshen.

Heretofore Egyptians had been sailing the Nile in Fellucas, simple boats that they handled adeptly. These boats could not be managed on the high seas for they lacked keels. They could ill withstand the buffeting of ocean waves or be kept on an even course against capricious ocean currents. Egyptian boats were restricted to plying the placid waters of a river, or maneuvering along a shore in benign weather. The Aamu had long learned to affix a keel to stabilize their ships and make them more maneuverable and seaworthy. Seaworthy ships opened a new commercial arena for Egypt, heretofore prescribed by the unpredictable winds and waves of the high seas.

Egyptian international communication and trade were also enhanced when the Aramaic language and writing of the Aamus displaced Akkadian as the lingua franca of the region.

Wheeled vehicles appeared from the East, and the horses and oxen to draw them. The introduction of the wheel to Egypt wrought radical changes. The donkeys upon which the Asiatic merchants had been portaging goods into Egypt over many hundreds of years were now joined by magnificent, swift horses who pulled heavily burdened wagons with ease and dignity. Until the time that Joseph's people are said to have settled in Egypt, Egyptians were obliged to transport heavy loads on their backs, or on sledges dragged laboriously over the sand, or at best, over rollers. The people of Egypt were awed by the horses, enormous yet amenable new animals harnessed to haul heavily burdened carts with proud dignity. They were astounded by the ungrudging behavior of these grand beasts, and by how manageable they were. They had never seen such animals, let alone believe that they could be made to do man's bidding.

Wheeled chariots were also introduced, outfitted for hunting or for war. Chariot parts were made of different woods, all of which came from Canaan and were known in Egypt only by their Semitic names. Chariots were ill-adapted to the sands of Upper Egypt, but well suited to war in Asia, a fact that eventually brought misfortune to the Aamus, who came to suffer for having introduced these weapons of war. Semitic charioteers continued to be employed in Egypt long after the Hyk-Khase were driven from Egypt and their people enslaved, and the care of the horses continued to rest in Aamu hands.

The wheel made the potters of Egypt more productive. They had previously wound coils of clay to the form of a vessel and then smooth the ribbed surfaces to shape, or pounded clay with firm fists into hollow bowls. Now, working with a wheel that whirled its clay burden swiftly around, the subtle fingers of the potters could lightly tease the pliant wet mass to form and work their wares with new-won ease into elegant shapes.

Not least among the many marvelous materials with which the Egyptians were made acquainted during the time of Aamu rule was a diversity of metals. Silver was more precious than gold in Egypt. A pure form of silver, smelted from argentiferous Asian ores, was imported from the Ararat mountains of the Hurrian land of Mitanni, and from the Zagros mountains of the Hittite land in Anatolia. The quality of Egyptian copper implements was improved by the addition of arsenic to copper, a process the Egyptians had never employed. The Egyptians were taught to alloy copper with tin borne in on the backs of asses into Egypt from the far-off mountains of Badakhshan, five thousand kilometers away. This magic metal transformed copper into a new, harder and more durable metal, bronze. Bronze tools could be honed sharper, they were longer lasting and more penetrating because the tools could be lighter an wielded with more force

The structure of axes and sledges were changed. The Aamus taught the people of Egypt how to set the helve, or handle, into a socket through the head, instead of tying the head crudely on it. This new method of attachment likewise allowed tools to be wielded more forcefully, for the handle would not split as easily and the head would not fall off.

Weapons were also changed in design and function. The shape of scimitars, swords and daggers were modified to make them more effective, and the composition of the metal was improved to make them sharper and harder.

The simple bows the Egyptians had been using were no more than a stiff stem bent back into a single arc. They were replaced by the far superior Asiatic bows that were constructed of laminations of wood and bone cunningly layered and molded into a composite curve. The reverse curves at the ends of these bows and the reinforced construction added power, range and accuracy to the weapons. The Egyptians were then shown how strong sinews would accommodate increased tension. The wood with which the bows were made was generally of foreign import. The Metropolitan Museum in New York, for example proudly displays one such bow, "a powerful, long-range weapon of Asiatic design which in Egypt had only recently begun to replace the old, one-piece self bow of the Middle Kingdom and earlier periods.13

Egyptians were also taught to carry arrows in a quiver, rather than clutch them clumsily in their hands as had been their custom heretofore.

The use of scale armor was another Aamu innovation. The war helmet, an Asian novelty, became known as the khepresh, the "Blue" or "war crown," worn by the Pharaohs. The armor and helmet was put to use later when the "Warrior Pharaohs" invaded their Asian neighbors.

The production of fabrics made from flax introduced from Asia by the earliest pre-dynastic settlers from Southwest Asia (Fact Paper 10-I), was enhanced by the introduction of Asiatic spinning devices. The upright loom, long known in the lands to the east, revolutionized the Egyptian weaving craft. As productivity increased, the cost of fabrics fell and they

became universally available. New fibers and new fast dyes made the fabrics more durable and colorful and added another dimension to the quality of Egyptian life.

One of the greatest benefits of trade with Nubia was the introduction into Egypt of the cattle native to that southern land. Another great beast was brought to Egypt during the Hyksos period. The hump-backed cattle, or zebu, from India, were bred to be well adapted to the climate of the area. These hardy beasts did not require extensive range, for they made efficient use of available fodder. The cows supplied milk, cheese, and meat to a hungry population, and the oxen were excellent for pulling plows, an onerous labor that had heretofore been performed by men. No longer would the fellahin, back bent, straining against the straps that leashed him to a wooden plow, fall faint from exhaustion in an effort to grow a little grain. The zebus made excellent draft animals and performed useful work such as the lifting of the waters of the Nile and its canals into the irrigation ditches by means of levers and turnstiles. It is interesting that modern Egypt still employs the Mesopotamian shaduf, a counterbalanced lever device for transferring large quantities of water from the Nile into Egypt's ever-thirsty irrigation system.

The Egyptians had not been altogether ignorant of the use of animals in place of men. They had learned from the Nubians that the long-horned Nubian cattle were of use in plowing, and scenes of crude wooden plows leashed to the horns of single cows are to be found in earlier Egyptian iconography. The introduction of the Aamu of the two-handled plow, of teams of zebu oxen with new methods of yoking made plowing far more efficient. The largest relief in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, taken from the fore-hall of a Theban tomb, illustrates the radical changes that took place under the Hyksos. William C. Hayes notes that "The yoke of the interesting, two-handled plow is not lashed to the horns of the beast, as was the Egyptian custom, but rests upon their necks forward of the up-projecting humps. Even more extraordinary is the two-wheeled oxcart appearing in the [same] register."14

Thus, instead of carrying Asiatic grains such as wheat or barley in hampers hung over the shoulders of the fellahin, or in bulging bags slung over Asiatic donkey's backs, great loads were laded onto a wheeled cart with open-latticed sides and driven to the threshing floor. The cart moved on four-spoked wheels similar to those of chariots, but of sturdier construction.

The barnyard fowl, or chicken, had been, like zebu oxen, domesticated and bred in India, and had likewise been known in Akkadia for a thousand years and almost that long in Canaan. The cackling hens astonished the farmers of Egypt by their productivity as they were observed clucking with satisfaction as they daily deposited another egg. So astonishing was the proliferate performance of these fertile fowl that Thutmose III had inscribed in stone his perplexity and amazement at the fecundivity of this "foreign fowl which gives birth every day!"15

Another Asian animal that the Aamu introduced into Egypt during Hyksos rule was the camel, a beast that is now employed as an ikon of Egypt!

Asian fruit trees were planted in Egypt by the Aamu. Pomegranates and figs added sweetness and variety to Egypt's diet. Olive trees were introduced, the fruit of which improved that diet, and the oil of the olives enhanced Egypt's culinary arts. New grains and vegetables were cultivated, plants that could survive the dry heat of that climate, plants that adjusted the balance of Egyptian nutriment.

Some Asian plants permitted the rotation of crops, an agricultural innovation in Egypt. Several crops could be planted in turn, and because the climate in parts of Egypt stays warm all winter, crops could be rotated even within the space of a year. The balance of the soil was thus maintained, and a with irrigation water available during th dry season fuller use of the nutrients supplied by the Nile was made possible.

New and decorative floral plants from Canaan began to appear in Egyptian iconography during this period. The cornflower, a common Canaanite flower, became a favorite of future Pharaohs and their tomb painters employed them lavishly. The breadfruit tree (carob) arrived somewhat later from Canaan and its fruit became a staple of Egyptian diet.

The widespread use by Egyptian nobility and commoners alike of the anthropoid coffin made a noteworthy change in Egyptian burial customs. "Introduced in the last quarter of the Twelfth Dynasty (the presumed time of Joseph's tenure as viceroy)... the coffin as a sort of rectangular wooden house is replaced by the anthropomorphic case decorated to represent the deceased."16

These new coffins were made possible by the introduction of new woodworking techniques and imported woods. Egyptian craftsmen had heretofore carved coffins from the coarse-grained logs of the sycamore-fig tree, much as primitive canoes are carved. The more sophisticated Asiatic carpentry and the new availability of suitable woods quickly brought the anthropoid coffin into Egyptian popularity. The introduction of tenoning, and other advanced woodworking techniques made the intricately constructed sarcophagus possible and cheap enough so that even a moderately well-to-do Egyptian could afford a set of two nested one within the other.17 The joinery employed in Egyptian coffins from that time forward was in sharp contrast to the crude, adze-carved Egyptian coffins that had preceded them.

The decoration of the first of these coffins employed the enveloping wing of the fabled Mesopotamian griffin, This design and the coffin form survived and are universally and ironically recognized as "Egyptian" no less than is the Asiatic camel!

Tenons and dowels were newly employed in constructing furniture. Tables and chairs and other furnishings produced with new, well-ordered cabinetry appear during the Hyksos period. A typical table is well-represented in the Metropolitan Museum of art. Its top is composed of joined hardwood boards, miter-framed on four sides and supported by a crowned cavetto-and-torus cornice. Its legs are skillfully keyed into the aprons with pegged. tenons. Stools with plaited rush seats are also found in association with the Rishi, or man-shaped coffins. "An article of furniture which did not come into use in Egypt until well into the Eighteenth Dynasty."18. Veneering is another sophisticated Asiatic technique introduced during the Hyksos period . Chair legs and other surfaces were thereafter often overlaid with exotic Asiatic woods such as the tamarisk, as well as with ivory.

Even the wooden pillow was an innovation of the Hyksos period!

The Aamus also enhanced the gentler arts of Egypt, its music, its dance, and even its games. New musical forms appeared, made possible by the introduction of a variety of Mesopotamian musical instruments. The multi-fretted lute and the multi-stringed harp, both equipped with an elaborate system of tuning, gave music wider scope and flexibility of tone. The lyre was regarded as a "foreign" instrument long after Hyksos rule had come to an end. It was always represented in Egyptian iconography as being played by a Canaanite woman. The oboe, with numerous closely spaced finger-holes, and the tambourine and other variations of Asiatic instruments brought Aamu music rapidly into Egyptian fashion, for the beauty intrinsic to the musical arts is universally appreciated.

The names of the instruments were also borrowed from the Semites. Thus the Egyptians call the lyre a keniniur, a variation of its Semitic name With the new music came new forms of dance.. The graceful images of the performance by Asiatic dancers of these new dances decorate the eternal resting places of Egyptian nobility. Images of the "foreign" instruments being played by pretty Asiatic courtesans or slaves were thereafter incorporated into the iconography of Egyptian tombs, so that their Egyptian occupants might not lack the sweeter attributes of life in their netherworld existence.

Egyptian nobility also had Mesopotamian games placed in their tombs with which they could eternally amuse themselves. The Aamu had introduced games played with the astragal, a form of dice, made from the tarsal joints of some hoofed animals (and incorrectly dubbed "knucklebones"). They were employed in "twenty squares," a game similar to the Indian parchesi. They were also used in senet, "the game of thirty squares," an even more ancient Asiatic game. The back of some senet boxes sport the layout of another Asiatic introduction, a companion game called tjau ("robbers"?), a game that Akkadian traders had also introduced into Karums, trading settlements they established in Anatolia.

The signet ring and the earring were newly adopted by the Egyptians during the Hyksos tenure, and Mesopotamian toiletry became a new Egyptian art. The introduction of bronze made mirrors possible, and the new, far more utilitarian alloy made a number of delicate grooming instruments possible. Bronze tweezers first appear in Egypt, and a "tweezer razor" came into use in the ladies wardrobe. It was a hair-curling and trimming device in which a chisel-type razor is hinged to a hollow, pointed prong, allowing it to be maneuvered like a scissors or tongs. Combs and razors, heretofore a rarity appear in greater frequency in Theban tombs as the impact of the culture of the more hirsute Asiatics made itself felt up the Nile

Of all the events that took place in the time of the Asiatic chieftains, the most important was one that did not occur: There was no war of consequence in Egypt throughout the rule of the Semitic chieftains!

This singular fact has been misunderstood, or deliberately distorted, for it is said that during the time of Hyksos rule the power and influence of Egypt declined. How sad it is that power is measured by what is achieved by the force of arms, and not by what is obtained by peaceful intercourse. How unfortunate it is that prosperity of a country is measured by the quantity of loot wrested from neighbors and from subjected peoples, and not by the progressive principles and productive processes absorbed through amicable exchange. How absurd it is to gauge the wealth of a country by how many golden artifacts can be plucked from its ruler's tombs, rather than by the adequate diet of the dwellers in the land. How blind is judgement when the welfare of a country is assessed by the profligacy of its rulers rather than by the prosperity of its people!

The Adulteration of History

How does it happen that the quintessential progressive period of Egyptian history is dismissed as irrelevant? That the peoples responsible for it are ignored?

It is painfully apparent that too often museums were concerned more with the accumulation of artifacts rather than of facts. Tomb-robbing became the prerogative of private collectors, museums, archaeologists and even governments. It is not surprising, therefore, that insofar as few grandiose monuments and exotic accouterments were collected from the period of Hyksos rule, the plunderers were prone to pronounce that little of value was contributed by the Aamus, and that, perforce, Egypt's civilization went into decline during the reign of their six "appointed" chiefs-of-chiefs, the Hyksos.

Not all scientific obtuseness can be attributed to an obsession with royal emoluments. Anti-Semitism, prevalent through the nineteenth century and well through the twentieth, fostered a willingness to uncritically accept the tendentious claims of conquerors. Historians might well heed the advice of Herodotus, who made a leisurely trip far up the Nile. He was privy to information given to him by the priests, to lists of kings, and to surviving documents Herodotus makes it abundantly clear that much of the information gathered was hearsay and unconfirmed fables. Herodotus presented this material honestly as material promulgated and probably adulterated by Egyptian warlords. He anticipated a slovenly reading of his work and contemptuously addressed those who would not heed his warning:

"Such as think the tales told by the Egyptians credible are free to accept them for history. As for myself, I keep to the general plan of this book, which is to record the traditions of the various nations just as I heard them and as they are related to me."19

It is inexcusable that in this presumably enlightened era, the proselyting of Egyptian warlords and priests referred to by Herodotus, and the tales flagrantly promulgated by Manetho are persistently echoed. It is inexcusable that to the present day, mention of the fundamental progress made in Egypt by Judaic progenitors, even when acknowledged, is seldom accorded more than a footnote.

It is also important to note that geopolitics in the form of pan-Arabism has become another effective muddier of historical waters.

Lastly, what is still more unjustifiable is that historians blithely continue to confuse conquest with progress. Objectivity is overwhelmed by pomposity. It has always been the case that, in lauding the glorious achievements of conquerors, and in clucking with satisfaction over the wealth of rich artifacts scavenged from grandiose monuments and tombs, historians are prone to speak of that culture or era as having reached a height of cultural development. They skip lightly over the thousands slaughtered in the process of conquest. It seems like quibbling to consider the cities decimated, the country-sides ravaged, the peoples enslaved. It seems unimportant that under despotic rule people are grievously taxed or forced into slave or corvee labor. It is deemed trivial that a great proportion of a country's gross national product is consumed not in promoting the general welfare but in touting the glory of conquerors through the creation of the very works that grace the halls of museums.

Must we continue to judge a civilization by the size and opulence of its palaces and the elaboration of lordly tombs? By how profligate are its rulers?

Or should we measure a civilization by its dedication to peaceful pursuits? By the economic well-being of its people? By its cultural and technological achievements? By the freedoms its citizens enjoy?

If the Hyksos period is judged by the latter criteria, then it becomes evident that during this unique historical interlude, Egypt was vaulted into a new era of peace and prosperity in which it advanced enormously in every field of knowledge and endeavor.

Notes

Note: This essay is largely a condensation of chapters 4, 5, and 6 of The Eighth Day; The Hidden History of the Jewish Contribution to Civilization, by Samuel Kurinsky, Jason Aronson, Inc., 1994, 59-128. An extensive bibliography is given in the book, covering facts not included in the sources given below.

- F. Wenderf et al, Egyptian Prehistory; Some New Concepts" Science, 1969, 1161-1171.

- Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, vol. 2 as in The Works of Flavius Josephus, trans. William Whiston, 1983, 257ff.

- Sir Alan Gardiner, Egypt of the Pharaohs, Oxford Press, reprint 1979, 156-7.

- Gardiner, Idem.

- Gardiner, Ibid., 137.

- Josephus, Against Apion, 163.

- Cyril Aldred, The Egyptians, reprint, Thames and Hudson, London 1984 139.

- Gardiner, Ibid., 165.

- Zaccariah Sitchin, article in The Jewish Week and Examiner, July 22, 1983.

- Herodotus, Persian Wars, 2.149.

- Zaccariah Sitchin, Idem.

- Sir Alan Gardiner. Egypt of the Pharaohs, Oxford Un. Press, reprint, 1975, 35.

- William C. Hayes, The Scepter of Egypt, part 2, The Hyksos Period and the New Kingdom, (1675-1080 B.C.E., Metropolitan Museum of Art, rep. 1968, 29.

- Hayes, Ibid, 165,

- Egypt's Golden Age, catalog of the exhibition "The Art of Living in the New Kingdom 1558-1085 B.C." Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, 1982, 16, 161.

- Aldred, Ibid., 143.

- Hayes, Ibid. 414.

- Hayes, Ibid. 27.

- Herodotus, The Histories, 178.