Glassmaking: A Jewish Tradition Part IV: Introduction Into England

Fact Paper 6-IV

© Samuel Kurinsky, all rights reserved

- "Tramps" of the Diaspora

- Early Glassmaking in England

- Who Were the Near-East Glassmakers?

- Capture of Glassmakers by Crusaders

- Refuge in the Netherlands

- English Glassmaking and the "Huguenots"

- The "Huguenot" Lorrainers

- Notes

"Tramps" of the Diaspora

Glassmakers were notoriously migratory. From ancient well into modern times the products of their fiery furnaces were avidly sought at the upper levels of society. Noblemen offered tempting enticements to induce masters of the secret art of glassmaking to practice their expertise within their fiefs. Noblemen went to great lengths to keep the glassmakers within their province, even conferring noble status upon both the glass-masters and their art. Yet glassmakers were prone to abandon their privileges to go on the move, even when it was clearly against their economic interests.

Glassmaking devolved around a single or, at most, several families. The security of glassmakers lay in their ability to maintain the secrets of their discipline. Glassmakers harbored little fealty to the countries within which they resided. The patriotism of glassmakers appears to have been confined to their art and to the community of glassmakers at large.

The Venetian Republic launched the most notorious attempt to contain the glassmakers and their art. Venetian glassmakers were confined to the island of Murano, far out in the Venetian lagoon. The Republic's ruling Council of Ten imposed strict statutory restrictions against the practice of the art outside of Venice. Severe punishments were prescribed for masters who defied the statutes. A Duke of Venice, while he was as yet the ambassador to France, was instructed to assassinate an errant master of the art who refused to return to Venice. The Doge-of-Venice-to-be personally carried out the assassination of the truant glassmaker.

The statutes proved to be temporary constraints, and were ineffective in the long run. In Murano the community of glassmakers passed guild statutes that denied the right of stranieri ("outsiders" - including native Venetians!) to apprentice at the trade. Marrying an "outsider" was deemed treason to the trade and a betrayal of the glassmaking community. In startling contrast, however, the Murano glassmakers freely shared their art and intermarried with glassmakers in and of alien lands. Glassmakers were universally accepted as part of the extended glassmaker's family.1

On the opposite flank of Italy, the glassmakers of Altare, the Piedmontese counterpart of the Venetian glassmakers, likewise maintained a barrier between themselves and the paesani around them. As strict as they were in insulating their art from their local neighbors, so remarkably accommodating were they to immigrant glassmakers from Spain, Pisa, Venice and elsewhere, and so freely did they intermingle with their foreign counterparts in the European diaspora.2.

The Near-Eastern provenance of all European glassmakers suggests a reasonable explanation for the subliminal binding force between the divers families of glassmakers. Their progenitors were likely to have shared a common Judaic genealogy. The Judaic concordance is likewise visible in the pattern of movement of glassmakers through the European diaspora. When juxtaposed with the movements of Jews through the same Diaspora the routes prove to be peculiarly parallel. Both the timing and destination of the movements of the two groups are remarkably congruent.

The glassmakers of the Levant are easily identified as Jews. In Europe, however, circumstances preclude facile identification. Glassmaking requires vast quantities of fuel, available only from extensive forests. Jews could not own land. As glassmakers they were entirely dependant on wood from the estates of the church or of feudal lords. They were compelled to contract with estate owners for the right to fell wood from their forests. They were obliged to work and live in or near those forests. Consequently they found it difficult to maintain contact with their co-religionists in urban environments.

In addition, the main market for glassware was not among the Jews. Stained glass windows, glass tesserae for mosaics, and church vessels such as chalices consumed a major portion of the glassmaker's production during the medieval period. The exigencies of the market in addition to dependency on access to church forest lands placed glassmakers at the mercy of the church. The increasing affluence of noblemen and the bourgeoisie with the advent of the Renaissance enhanced the market among the rich and powerful. The fate of glassmakers thus hinged on the good-will of the Christian hierarchy, both ecclesiastic and secular.

Jews were regularly expelled from the countries in which they resided. Jewish glassmakers found it difficult to obtain usufructuary rights for cutting wood from forests as Jews. Their ability to obtain large quantities of fuel, a vital necessity, usually depended on being deceptive about their religious leaning. Many ruses were used. Jewish glassmakers in Spain took on a Catholic disguise. These Marranos secretly carried on their Jewish faith in Spain, and continued their deception upon emigrating into other potentially hostile Christian environments.5 Many who stayed in Spain as "New Christians" likewise secretly maintained their faith, and continued to do so over many generations.

Other stratagem were employed to enable glassmakers to live and work in oppressive environments. In Protestant territories where Huguenots were granted refuge but from which Jews had been expelled, Jewish glassmakers managed to practice their art by identifying themselves with that Christian sect. Significantly, the art of glassmaking was absent from England during the period of the Jewish expulsion. It will be seen below that glassmakers with Sephardic or other names of Judaic origin, assumed a Huguenot facade in order to make their fortune in England.

Early Glassmaking in England

There are traces of glass-working activity in England during the 355 years of Roman occupation. The evidence suggests that imported cullet (broken glass) or imported raw glass was employed at these sites. The cullet was remelted and fashioned for making windows. Traces of furnaces that produced glass products were found in Wilderpool, in Lancashire, near Warrington, Caistor, near Norwich and possibly at several other sites.4 During the Roman period (as two Roman emperors testified), Jews were the only people practicing the art of glassmaking.5

In the Dark Ages the practice of the art of glassmaking dimmed virtually to extinction in western Europe. It disappeared entirely from England. Its absence is confirmed by the predicament of Bishop Biscop, founder of the Abbey at the Monkwearmouth monastery, constructed in 676. A contemporary chronicler reported that:

When the work was drawing to a conclusion [the Bishop] sent messengers to fetch makers of glass, who were at that time unknown in Britain, to glaze the windows of the church, its side chapels and clerestory.6

Not a single mention of glassmaking activity appears in English archives until 758, when Cuthbert, the Abbot of Jarrow, sent an urgent request to the Archbishop Lullus of Mainz to assist him in obtaining glassworkers. His plea defines the status of the art throughout northern Europe as clearly as it does of England:

If there be any man in your diocese who can make vessels of glass, pray send him to me; or if by chance he is beyond your bounds, in the power of some other person outside your diocese, I beg your fraternity that you will persuade him to come to us, seeing that we are ignorant and helpless in that art.

Where the bishop found the "foreign glassmakers" to work at Monkwearmouth is unknown, but traces of furnaces were found on the site in the late 1960's by Rosemary Cramp.7 The art did not root. The practice of glassmaking does not reappear until the turn of the 13th century. Yet, as the Middle Ages progressed, the possession of elegant glassware became essential to a nobleman's status. No self-respecting nobleman would be without the exquisite glassware imported from the Near East.

Who Were the Near-East Glassmakers?

We are fortunate to be able to identify the Levantine glassmakers who were producing the glassware imported into Europe during the dark period. The Arab geographer, Al-Mudqadassi visited Tyre around 985. The chronicler reported that Tyrian exports included glass beads, bracelets, and excellent wheel-cut glass.8

The high regard in which Tyrian glass was held was confirmed by no less a personage than William of Tyre. The 12th century ruler extolled the exquisite vessels being "carried to far distant places and which easily surpass all products of this kind."9

The Bishop of Akko (now Acre) was equally enamored with Tyrian glass. He wrote sometime before the year 1240: "In the territory of Tyre and Akko the purest glass is made with cunning workmanship out of the sands of the sea."10

Who were the producers of this luxury glassware? There are occasions in which the fortuitous presence of a witness casts an illuminating beam into the otherwise impenetrable murk of an ancient period. Such a witness was Benjamin of Tudela, one of the adventuresome merchant/scholar globetrotters of the times. Benjamin visited the Levant at the end of the 12th century. We can confidentially identify the glassmakers of Tyre, Antioch, and Damascus through Benjamin's eyes..

"The Jews own sea-going vessels," reported Benjamin about the Jews in Tyre, "and there are glassmakers among them who make that fine Tyrian glassware which is prized in all countries." Thus, in a single sentence, Benjamin illuminates a vital portion of the history of commerce, of a people, and of an industry. Benjamin goes on to describe Tyre as a magnificent port in which traders "from all parts" are active. "About 400 Jews reside in this excellent place," Benjamin reported, referring to heads of families representing a population of some 2000 Jews. One of the heads of the Tyrian community, Rabbi Meir, came from Carcassone in Provence. Therein is revealed the international character of Jewish life of the times.11

Similarly, Benjamin reported on the glassmaking activity of Jews in Antioch and Damascus. In Antioch there were ten heads of families "engaged in glassmaking." Benjamin's observations are reinforced by the correspondence of Jewish artisans and merchants of the area with the Jews of Fustat (Old Cairo) and from other documents recovered from the geniza (storage room) of the 1100-year-old Ben Ezra Synagogue of that city. The synagogue was visited by Benjamin in 1169.12

The documents register the value placed on the excellent quality of glassware being produced in Antioch, Tyre and Beirut and reveal the identity of glassmakers and/or dealers. Fustat was a center of glassmaking, but better quality glass was being imported into Fustat from the Levantine cities, especially a red variety of glass. The production of this unique red glass seems to have been the secret of the glassmakers of Beirut.13

Typical of the transactions between Jewish dealers and artisans of the two areas is an order for "37 baskets of Tyrian glassware" which had been delivered to Fustat. The document records how Khalaf ben Moses ben Aaron, the representative of the merchants of Tyre, conferred the power of attorney in an action to collect payment for the glassware.14

That the Jewish quarter of Fustat was a center of glassmaking was confirmed by American excavations in Fustat under Professor George T. Scanlon. Traces of glassmaking facilities were found in an area that spanned the Jewish quarter. A large variety of vessels of local manufacture, dating from as early as the eighth century, were uncovered throughout the ruins. The wide range of styles and functions were clearly directed at a wide and varied market. They consisted of utility wares such as bowls, bottles and goblets as well as items with specific functions such as chalices, toilet bottles and cupping vessels. Products manufactured for the state or its officials were also found, typical of which were a glass weight with the imprimatur of Egypt's finance minister and a glass jeton, a token used in accounting, bearing the name of the Fatimid Caliph al-Zahr (1021-1035).15

Capture of Glassmakers by Crusaders

The Crusades brought the wielders of the cross and the sword into contact with eastern glassmakers. The Norman Crusader, Prince Bohemund of Poitiers, Master of Antioch, and the Piedmontese Marquise Montferrato, Prince of Jerusalem, transported glassmakers from Palestine and installed them into their European fiefs. Another Norman Crusader, Roger II, obtained his glassmakers in an invasion of Byzantium, and implanted them in his fief in southern Italy. The Venetian Dukes enticed Jewish glassmakers working in communities around the Adriatic to relocate in their lagoon. Glassmaking zoomed to a high art in Venice and Altare.16 By the middle 14th century, owning an array of glassware produced in these two glassmaking communities became part and parcel of achieving a status worthy of a lord.

The English Crusaders, however, missed the boat, 3

Not a single glassmaker was brought to England from the Levant. English noblemen and church officials were humiliatingly obliged to purchase glassware from the Venetians, or the Altarese, or from the Near East through the agencies of their Christian rivals.

A Scottish legend recounts a dramatic action by the Earl of Moray to impress the Patriarch of Venice at a banquet given for his eminent guest. The table was elaborately set with Venetian glassware of considerable worth. Professing that the sparkling array of glassware was not executed to the highest Venetian standards, the Duke demonstrated his artistic sensibility by ordering his servants to pull the tablecloth from the table, sending the sparkling glassware crashing to the floor. The table was reset with even more exquisite tableware from which the Earl smugly served his astonished guest.17

As the rumblings of the Renaissance heralded the dawn of a new age, the English became ever more frustrated in their efforts to secure artisans capable of turning out artistic glassware. King Steven (1135-54) managed to entice one glassmaker to practice his secret art in England by offering the most remarkable benefits:

King Steven appointed a glassmaker named Henry Daniel to be the prior of one of the mot important monasteries. That was indeed, an honour and certainly a strange one for two reasons. Firstly, Henry Daniel was not a monk - he was a layman! - and secondly he was married! But those things didn't seem to have bothered the King's conscience much, in fact, King Steven said that if only that glassmaker had been able to sing Mass he would have made him Archbishop of Canterbury.18

King Steven "made Henry Daniel, vitrarius, a "Prior of St. Benet's at Holme, at that time perhaps the most influential monastery in Norfolk or even in England."19

Who was this "Daniel?" We have no further information about him, but it is significant that he appeared in England at the very time in the early 12th century when a new tolerance of Jews was instituted. Jewish merchants and artisans were welcomed in the city of Oxford, for example, while the University was in its infancy. The Jews settled in the center of the town, as a plaque affixed to the wall of the city's central public library on St. Altdate's Road attests.20 The cemetery of that ancient Jewish community was covered over after a subsequent traumatic period. It is now part of the Oxford Botanical Gardens, the oldest in England.

A few more descendants of the eastern artisans who had been brought to Normandy by Bohemund made their way to England in the early 13th century before the expulsion of the Jews. Notable among these enterprising foreigners was Laurence Vitrearius ("Larry the glassmaker"), who was dubbed "The Father of Wealden Glassmaking."21 A deed of 1226 gives Laurence title to property at Chiddingford in Surrey for the purpose of erecting a glassmaking facility. King Henry III retained Laurence to outfit the new Westminister Abbey with crystal and colored glass. As a result of the enterprise initiated by Laurence and continued by his sons, William le Verrir and Richard de Dunkhurst [!], Chiddingford was granted a royal charter in 1300. The family of the founder, however, mysteriously disappeared from English chronicles a year later. It is presumed by historians that one of his sons "returned to his own country" leaving the glasshouse and a considerable estate to his brother "le Verrir." The country he returned to is unspecified.

The disappearance of the pioneers of English glassmaking coincides with a reversal of the fortunes of Jews in England. The Jews were enjoying a growing prosperity until a series of anti-Jewish decrees led to violence. In 1244 the students of Oxford launched vicious attacks on the Jews. A plaque on the Oxford campus "tells of a Deacon who converted to Judaism, married a Jewish woman, and was later burnt alive for this 'crime.'" The first great expulsion of the Jews in the Middle Ages took place a few years later.

The quality of products and the productivity of the Chiddingford glassworks degenerated after the disappearance of Laurence and his brothers, and coinciding with the period in which Jews were banned from England. The English glassmaking industry bumbled fitfully along for the next two and a half centuries.

A few glassmakers did manage to shortly rejuvenate glassmaking in England during the period of Jewish banishment. The Schurturre family arrived in Chiddingford from Normandy shortly before 1343. They were followed by the Peytowe (Peto or Poitou) family, whose surnames, being variant English transliterations of Poitiers, identifies the family as hailing from that Norman province. The surname reveals a curious finale to the saga of the glassmakers as they passed from Palestine to Byzantium to Normandy and, finally, to England.

As was noted above, glassmakers were brought to Normandy from Palestine during the reign of Prince Bohemund over Antioch.

Another Norman Crusader, Roger II, ravaged Christian Byzantium, where he captured the silkmakers of Thessalonika and Thebes and the glassmakers of Corinth and transported them to his domain in Southern Italy and Sicily. The crusading French King Louis VII formed an alliance with Roger II. Louis divorced his wife, Eleanor of Acquitaine, who then became the wife of Henry II of England. Eleanora's daughter, Marie, Countess of Champagne, held court at Poitiers!22

Thus the connection was made between Poitiers, where imported Near-Eastern glassmakers were at work, and England, a nation desperate for glassmakers.

Altare was another source of adventuring glassmakers. An Altarese, Nicolo Greno, was a glassmaker mysteriously found outfitting the Norwich cathedral.

England continued to import virtually all of its glassware despite intermittent successes at enticing a glassmaker to its realm, . The humbling situation inspired a poet to pen a grateful tribute to a lone glassmaker at work in Chiddingford. Ruth Vose quotes it to illustrate the fact that "British glasshouses were still few and far between" with a contemporary poem from Carnock's Breviary of Philosophy:

As for glassmakers, they do be scant in the land

But one there is as I do understand

And in Sussex is now his habitacion

At Chiddingford he works of his occupacion

To go to him it is necessary and meete

Or lend a servante that is discreete

And desire him in most humble wise

To blow thee a glass after thy devise.23

As the sixteenth century unfolded, England remained desperate to obtain glassmakers who would teach the trade to Englishmen. No Englishman succeeded in breaking into the cocoon that glassmakers had woven around the secrets of their art despite the generous rewards offered for glassmakers to fire their furnaces in England.

In 1515, the Venetians decided to allow the Jews to come back to Venice. The Jews asked to re-establish themselves among the glassmakers on the island of Murano. The request was denied, and an abandoned foundry, the Geto, was assigned to the Jews.24 Thus the glassmakers confined to Murano remained isolated.

A business man from Antwerp, de Lame, enticed by the extraordinary inducements tendered by King Edward VI, convinced eight Murano glassworkers to relocate in England. The Venetian Council of Ten thereupon passed a special edict on September 18, 1549, recalling the "truant craftsmen." The threat of dire punishments to be meted out not only to them but to their families at home frightened the artisans. As they prepared to return to Murano they were arrested by the English king. They stayed locked in a tower until they agreed to perform a glassmaking stint of eighteen months duration in England before they would be permitted to return home.23A King Edward's aspirations for capturing the art were dashed. No Englishman managed to learn the secrets of the trade from the errant Murano glassmakers. All but one returned home after completing the term.

His name was Joseph Caselari, and he left England in 1569 together with a partner, Thomas Cavato of Antwerp, to join the rising industry at Liège.

Refuge in the Netherlands

The turmoil enveloping the European Christian world in the sixteenth century profoundly effected glassmakers, and opened a way for England to solve its dilemma.

The new Protestantism began by Luther in Germany about 1517 spread rapidly in France. Followers were accused of heresy, and a General Edict urging their extermination was issued in 1536. Nonetheless, Protestant groups continued to sprout. The first "Huguenot" church was founded in a home in Paris about 1555, based on the teachings of John Calvin. Its influence spread among the French, leading to an escalation in Catholic hostility. Finally, in 1562, some 1200 Huguenots were massacred at Vassey, France, thus igniting the French Wars of Religion which would devastate France for the next 35 years.

Huguenots and Jews came increasingly under Catholic attack. Both groups found refuge in the Netherlands, and its cities quickly became major glassmaking centers. Jewish industries were established in Liège, Antwerp, and Amsterdam. and they flourished as Dutch international trade burgeoned. Jewish merchants, in concert with their congenial Dutch hosts, created a sea-going, world-wide trade network that became a formidable rival of the Venetians, the Portuguese, the Spanish, the Genovese, and the English.

Facon de Venice glassware and the more practical but equally sophisticated facon de Altare glassware was produced in Liege and Antwerp to cater to the appetite of the European upper classes for exotic and pretentious products. Amsterdam turned largely to the production of trade beads as new opportunities burst into being with the discovery of the Americas and the world-wide expansion of colonialist trade.

The Jewish quarter of Amsterdam, the Waterlooplein, became a bustling beehive of bead production. Archaeologists unearthed evidence of a number of major glass bead industries in the heart of the old Jewish quarter, preserved through a stroke of good fortune. Between 1593 and 1596 the level of the land at Waterlooplein was raised to make the area more habitable.25 The "layers of clay and city refuse" used to bring the level of the land higher and drier, preserved within them a massive assortment of artefacts relating to a major glassware and glass bead industry.

Four sites were identified, all within the confines of the Jewish quarter. One of the sites was over 70 meters long. Over 50,000 specimens were recovered, evidencing a robust glassware producing industry. Chunks of raw glass, charred and vitrified crucible fragments, incomplete and malformed parts, and all sorts of other manufacturing detritus make the substantial size of the industry and the expertise of its practitioners clearly evident. The production of trade beads appeared to have been the main activity. An examination of 15,136 samples disclosed that the group was composed of 30 major types and 290 varieties of beads.26

Beads exhibiting distinctive Amsterdam-made characteristics were employed by the Dutch and English in the early North American fur trade. They have been recovered from Five-Nations Iroquois, Onondaga, and Susquehannock tribal sites. From 33% to 53% of all the Amsterdam bead varieties identified in the sampling of the more than 15,000 beads noted above, "make up from 42% to 71% of these sites' bead collections.27 From Ontario to Virginia, Amsterdam-type beads were a staple item of English and Dutch trade goods.

A significant proportion of beads found in Florida's Indian sites are likewise characteristic Amsterdam varieties. Likewise, of the 348 beads recovered from an Indian village site at Radford, Virginia, 83% of the beads, "and at least 37% of the recorded varieties have counterparts in the Amsterdam assemblage. Of three striped varieties, two have Dutch correlatives."28.

The $24.00 worth of beads with which Manhattan Island was purportedly purchased would probably have been produced in the Jewish quarter of Amsterdam.

The unmatched quality and variety of the Amsterdam beads generated a thriving business in beads for the Netherlands in North Africa as well as in America. The Venetians were less advanced in certain technologies then were the Netherlands bead-makers. Notwithstanding that their elegant products were envied and imitated the world over, the Venetians turned to the glassmakers of the Netherlands for their bead-making expertise. Antonio Neri, a Florentine chemist, went to the Jews of Antwerp to learn their secrets.

Neri was a priest under the patronage of Don Antonio de Medici.29 He became renowned as the author of L'Arte Vetreria, the first printed book on glassmaking, published in 1612. In the text there are interesting parallels to a fifth-century, hand-written Hebrew book, El Lapidario, which had first been translated into Arabic, and then into Castilian Spanish. A number of virtually verbatim translations from the Castilian text appear in Neri's Italian text, as, for example, "The prettiest and most noble of all glasses... are those made in imitation of the colors of oriental gems."30

Neri sought to augment his knowledge of glassmaking from the Jewish glassmakers of the Netherlands. Neri started by corresponding with Emanuele Ximenes of Antwerp. In a letter dated January 17, 1603, Emanuele wrote to Neri that in order to obtain more information about the production of these beads, he consulted with [the Jewish glassmaker] Marten Papenbourg, "Having learned that only he deals in this merchandise and has a workshop where four furnaces were operating continuously and canes of every color were being produced." Neri wrote back, begging for samples, especially of a bead of a certain blue color with which the Dutch were doing a land-office business in Africa, where that particular colored bead was in great demand.31 In that same year, 1603, Neri moved to Pisa, and then to Antwerp, returning to Florence in 1612. Soon after his return he wrote the work that became the first printed treatise on the art of glassmaking.

Murano gained the knowledge of advanced bead production from Neri's book. It is evidenced, for example, by the incorporation of the word conterie ("fancy glass beads"), into Muranese vocabulary, a word employed by Ximenes in his correspondence with Neri. Papenbourg was located at the northeast corner of the Netherlands, lying presently just over the Dutch border in Germany.

During the era of colonialist expansion England became even more distressed about having to obtain trade goods from her competitors than for having to import fancy glassware to grace her noblemen's tables. The English government granted a Netherlander alchemist, Conrad de Lannoy, a most lucrative contract "to carry out a series of experiments and give instruction to the English glassmen in London who had been left to their own incompetence."32 The effort was a dismal failure. A report to Lord Cecil stated that "all our glasse makers cannot facyon him one glass tho' he stoode by them to teach them."33

Lannoy would have been well served to heed the advice of master glassmakers, who wisely point out that "If you seek to become a master glassmaker, you must first obtain a grandfather who was master of the art!"

A few glassmakers trickled in from France and Italy into the thickly forested Weald of Sussex and Surrey. The foreigners operated independently in the typical "tramp" mode of glassmakers, sealing the secrets of their art within their ranks. English authorities failed to cajole the "tramps" into relinquishing their secrets. The "tramps" came and went, and England remained devoid of what it avidly desired, a glassmaking industry.

English Glassmaking and the "Huguenots"

As the Huguenots came increasingly under Catholic attack, they joined the Jews who had taken refuge in the Netherlands. England's attempts to acquire artisans from the Lowlands were, at first, as frustrated as was its attempt to wheedle it from Venetian and Altarese glassmakers. So long as the possibility existed that Catholic Mary (Mary, Queen of Scots 1542-87) would succeed to the English throne, and so long as Jews were banned England, the Lowlands glassmakers were impervious to English enticements.

The demise of Catholic Mary sparked a new opportunity for England to obtain craftsmen from the Netherlands. Spanish efforts under Philip II to bring the Netherlands under Catholic control caused industrial turmoil, consternation among the Huguenots and the Jews, and sparked an exodus of artisans to England.

The Huguenots in France were largely "artisans, craftsmen and professional people."34 It is easy to understand that Jews identified with the Huguenots both as religious outcasts and as artisans, and that the Huguenots of the times were likewise prone to sympathize with the Jews. The weavers, dyers, and dealers in fabric, essentially Jewish trades, were notable among the trades shared by the two communities. It was so-called "Flemish clothworkers" who "brought the 'new draperies' to Colchester and other towns of East Anglia.35

The English door was now open for glassmakers, so long as they professed to be Huguenots, for Jews were still persona non grata in England. A Huguenot identity became a passport into a country that offered glassmakers unbounded opportunities.

A canny promoter, John Carre, seized upon the situation and came from Arras to Antwerp to make contact with glassmakers. It is noted in the Publication of the Huguenot Society that Carre "came hither for religion," which the Huguenots took to mean that he had emigrated as a Calvinist. The Society's records further record that Carre's daughter, Mary, was married to the cloth merchant Peter Appel "of the Dutch churche"36

Carre and family were well established in England in 1567, soon after Phillip II of Spain set up the "Council of Blood." "[The] agencies of fire and sword, outrage and massacre were at work in Flanders, where the butcher Alva was seeking to fasten the Spanish yoke on that country, with the result that many thousands of refugees sought asylum in this country [England]."37

Carre's entry into the English arena breached the dam that had held the English glassmaking industry to a trickle of inferior products. Carre avoided the mistakes of his predecessors. Instead of attempting to inveigle craftsmen to leave Venice, he gathered a competent crew from among the pool of glassmakers who had found refuge in the Netherlands. Among them were Venetians who had eluded the tentacles of the Council of Ten, Sephardim who had sojourned in Altare, Near-Easterners who had been brought to Normandy during the Crusades, and the Lorrainers whose origin traced back through Bohemia and Transylvania to Khazaria and Persia.

Netherlands Jews were caught in a vise of intolerance. They were wedged between the hard rock of England and the hard place of the Inquisition. The ban was in full force in England, but a way Jews could escape the clutches of the "Butcher of Alba" was by emigrating to England under a Huguenot cover, or by professing to no religion at all in the hope of passing unnoticed. The surprising numbers of glassmakers who did register as being "of no church" attest to the fact that the English, eager to capture the art, turned a blind eye to the ploy.

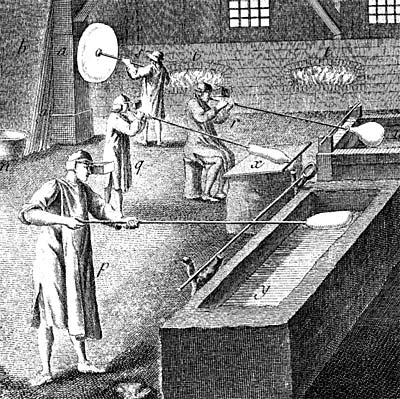

Reinforced with firm contracts and considerable capital, Carre set up operations at two locations. At Alfold in the Weald he took advantage of the expertise of the artisans from France in the manufacture of window glass [broad-glass] and common forest ware. He selected Crutched Friars near London for the production of crystal glass a la facon de Venise, the exquisite glassware that was the tour-de-force of the Venetians and the Altarese Carre's efforts were made effective by the virulent persecution of the "Reformers," climaxing in the massacre of St. Bartholomew in 1572 and the consequent exodus of several hundred thousand "anti-Papists" from France. The Tudor court of Elizabeth I made Huguenots welcome, and closed its eyes to the fact that artisans with Sephardic names were registering as "Huguenots," and that others were registering as being "of no church."

The first glassmaker to be engaged by Carre for his London operation was an Altarese, Ognia ben Luteri, in 1571.38 Luteri's name is explicitly stamped with the Hebrew determinant ben ["son of"], and translates to Ognia, son of Luteri.," a standard Jewish name construction. His name also appears in listing of eighteen Altare glassmakers who ended up in England, one of the few surviving documents of the Universitá d'Altare,.as the Altare community of glassmakers referred to themselves. The term Universitá was almost always used to define a Jewish community.39 Luteri paved the way for other glassmakers from Italy who followed under Carre's wing.

Another important glassmaker who came to England from Antwerp under Carre's wing was Jacob Verzellini. Jacob's surname was derived from the city of Vercelli. Jacob's passage through the Diaspora is a classic example of why both Jews and glassmakers were described as "tramps.". Jacob was born in Venice in 1522. He moved to Vercelli, located close to the glassmaking community of Altare, where he undoubtedly worked at the furnace. In typical Judaic fashion, Jacob thereafter identified himself as "Jacob from Vercelli," adopting the name of the town for his own. He then moved to Antwerp where he married a Dutch woman who bore him six sons and three daughters. Finally, Jacob arrived in England where he joined the Altarese master, Ognia ben Luteri, at Carre's London glassworks.

Jacob is credited with a major role in founding the glassmaking industry in England. "Mister Jacob" became "the pattern of all glassmakers and a great figure in our [English] industrial history. Jacob, registered as "Joseph, a Venetian and a glassmaker," was lodged in London in 1571 among six glassmakers, most of whom registered as "being of no churche." "Many liberties were taken with the Christian [sic!] and the surname of Verzellini by clerks who failed to 'get' the spoken word."40 The Huguenot Publication Society notes pointedly that Joseph (i,e,, Jacob) "was a member of the Italian churche but he never received communion until he came."41

After Carre's death in 1572, "Mister Jacob" took charge of the business. By 1575 Jacob was in control of two glassworks. He was "the first Italian and the first glassmaker who was able not only to obtain an official sanction but to establish a permanent and prosperous glass industry in this country."42

"Mister Jacob" expanded his staff with other employees from the Diaspora. They registered with the same anomalous religious notation. Domingo de Manelo, whose name clearly stamps him as Sephardic, specified that he was "of no church." Marcus Guado and "Marie his wief of no church" was another registry. The Spanish/Italian genesis of those names is also indicated in the name of Carre's right-hand man, Dominico (Domingo) Caselari.

That some of Carre's employees with similarly distinctive Sephardic names were registered as Huguenots cannot be interpreted otherwise than they were employing the French/Christian cover to circumvent the laws prohibiting Jews from residence in England.

Only one of all the glassmakers of the district in which "Mister Jacob" operated: "Nicholas Valarine, glassmaker and his wief and ii children," registered upon arrival in England as being "of the Italian church."

The "Huguenot" Lorrainers

Most notable among the "Huguenot" glassmakers who abandoned France and established themselves in England were members of all four of the families who had been granted noble status, the Gentilshommes Verriers of the Lorraine.43 The lineage of the Lorrainers traces back to Persia. The saga of their journey through the Diaspora starts with the association of their Persian progenitors with the Khazars. It continues with the introduction of their art by the glassmakers among them into Russia and Poland. After the conquest of the Khazars by Byzantines, ravaged by the Rus tribes and suffering under Byzantine domination, they moved into Bohemia and Transylvania.. Enticed by eager French noblemen of the Lorraine with extraordinary privileges they moved into the Lorraine in France. As Huguenots they escaped Catholic oppression and slaughter by relocating in England, where they were a major factor in making glassmaking a solid English industry.

Their saga and that of the glassmakers that followed them into England, will be told in the subsequent HHF Fact Paper 6-V, Glassmaking; a Judaic Tradition; An Industry is Brought to England.

Notes

1: HHF Fact Paper 29-I, The Judaic Origin of Venetian Glass; The Formative Period, and HHF Fact Paper 29-II, The Judaic Origin of Venetian Glass; An Industry of Foreigners.

2: HHF Fact Paper 25, The Glassmakers of Altare.

3: See HHF Fact Paper 5, Juan Robles and the Inquisition.

4: The History of the Glass Container, Glass Manufacturers Federation, London, 2

5: HHF Fact Paper 6-II, Glassmaking, A Jewish Tradition; The common Era

6: Rosemary Cramp, "Glass Finds from the Anglo-Saxon monastery of Monkwearmouth and Jarrow," citing Bede, Opera Historica, a late 7th century work ed. by C. Plummer, 1896, cap. 5; H.W. Woodward, Art, Feat, and Mystery, The Story of Thomas Webb and Sons, Glassmakers, 1978.

7: Dan Klein, Warren Lloyd, eds. The History of Glass, London, 1984, p. 45; Victor Wyatt, From Sand-core to Automation, London, 1978, 3, translates the page to read: "seeing that of that art we are ignorant and without resource."

8: C.J. Lamm, Mitalterliche Glaser und Steinschnittarbeiten aus dem Nahen Osten. 1929/30, 491, no.41, as cited by Anita Engles, Readings in Glass History # 1, Jerusalem, 1973, 21.

9: William of Tyre, A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea, trans. Babcock & Krey, , vol. 2, 6.

10: Jacques de Vitry, Palestine Pilgrims Text Society, Vol. 2 no II, London, 1896.

11: M. N. Adler, The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela, 1907.

12: Anonymous author, Ben Ezra Synagogue, Imprimatur WAHBA, Cairo, 1973.

13: Goitein, "The Main Industries of the Mediterranean area as Reflected in the Records of the Cairo Geniza," Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 1961, 187.

14: S. Asaf, Shtorim Antiqim min ha-Geniza, Tarbiz, 9 (Hebrew), as translated by Anita Engles, Ibid, 196-7.

15: George A. Scanlon, "Fstat Expedition, Preliminary Report, 1968," Jarce XIII, 1976, J.J. Augustin, New York. Wladyslaw Kubiak and George Scanlon "Fustat Expedition, Preliminary Report, 1971," Parts I nad II. George A. Scanlon, "Fustat Expedition, Preliminary Report, back to Fustat-A, 1973," Annales Islamologigues. t, XVII, 1981.

16 HHF Fact Paper 25, The Glassmakers of Altare; Fact Papers 29-I and 29-II, The Judaic Origin of Venetian Glass

17: Klein and Lloyd, Ibid., 91.

18: The History of Glass, a talk given to visitors of the Thomas Webb and Sons glassworks on June 1, 1981. The incident is detailed in a medieval MS The Story of Bacton, from Bromholm Priory, Norfolk, Vose, 103.

19: Wyatt, Idem.

20: Marc Shapiro, "Jews at Oxford," Congress Monthly, Nov./Dec., 1989, 11.

21: W. A. Thorpe, English Glass, London, 1935/49, 81.

22: V. H. H. Green, Medieval Civilization in Western Europe, New York, 1971, 185, 346.

23: Ruth Hurst Vose, Glass (Antique Collector's Guide) Crescent Books, 1989, 105.

23A: Klein et al, Ibid., 90.

24: Carla Boccato, "Licenze per altane concesse ad Ebrei del Ghetto di Venezia, LRM, March-April, 1980, 106.

25: Karlis Karklins, "Early Amsterdam Trade Beads," Ornament, 9 (2) 1985,36, citin: Jan Baart "Glass Bead Sites in Amsterdam," a paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Historical Archaeology, Williamsburg, VA Jan. 5-8, 1984.

26: Karklins, Idem.

27:.Karklins, Ibid., 40.

28: Karklins, Idem.

29: Harold Newman, An Illustrated Dictionary of Glass, London,1977, 213.

30: Antonio Neri L'Arte vetreria distinta in libri sette, 1612, LIV, ch. LX, 57.

31: Luigi Zecchin, "Lespatrio dell'arte," GE, no. 14,.1954. The letters of Ximenes are preserved in the Biblioteca Nazionale di Firenze, Fondo Magliabecchiano, XVI, 116.

32: Thorpe, 1924, 62.

33: Vose, Ibid., 106. See also T. Pape, Medieval Glassworkers in North Staffordshire, 1934, 12.

34: The National Huguenot Society, www.huguenot.netnation.com/general/huguenot.htm

35: Eleanor S. Godfrey, The Development of English Glassmaking 1560-1640, Un. Of Carolina Press , Chapel Hill, 1975, 23; L. Scouloudi "Alien Emigration into and Alien Communities in London, 1558-1680, Proceedings of the Huguenot Society of London, xvi, 1937-41, 27-49.

36: Godfrey, Ibid., 17; Publications of the Huguenot Society of London, vol. X in 4 pts. Un. Of Aberdeen Press, 1900-1908, pt.i, 263, 317, 390, pt. ii. 294.

37: J. Stuart Daniels, The Woodchester Glass House, Gloucester, 1960, 18.

38: Vose, Ibid., 107

39: HHF Fact Paper 25, The Glassmakers of Altare.

40: Thorpe, Ibid, 97.

41: Publication of the Huguenot Society, vol l, Lymington, Huguenot Society, 1893, x. ii, 41.

42: W. A. Thorpe, A History of English and Irish Glass, London, 1924, 75.

43: Thorpe, Ibid., 1935, 87, ""Carre's gentilshommes verriers belonged mainly to four Lorraine families - Hennezel (Henzey, Ensell), Thisac (Tyzack), Thietry (Tittery, Tyttery) an Houx (Hoe)... They were Protestants by faith and all the readier to accept Carre's offer of employment in Britain." After Carre's death, several of the Lorraine families joined forces with glassmakers from Flanders and Normandy.